exhibition

The days of small things

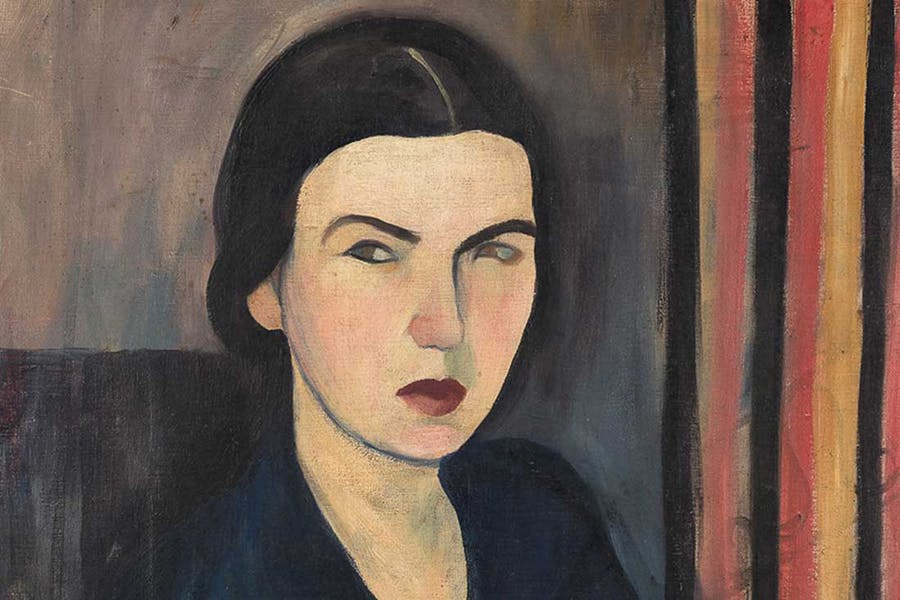

Sarah Affonso's work at Museu do Chiado

After ' Sarah Affonso and Minho's Folk Art ' at Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea do Chiado shows the work of one of Portugal's most notable modernist artists - 120 years after her birth. 'The Days of Small Things ' will run until March next year.

Despite a multifarious work covering design, painting, illustration, ceramics, embroidery and furniture/interior decor, Sarah Affonso remains, 120 years after her birth, relatively unknown to the public. Her marriage to the Promethean figure of Almada Negreiros and the fact that she was born in a country that raised serious obstacles to female artistic expression have greatly contributed to this fact.

However, Sarah was one of the first to overcome such obstacles to the affirmation of women as artists in Portugal, back in the early decades of the twentieth century. She was the first woman to frequent – against all conventions – Café Brasileira in Chiado, which reveals not only the prejudices of her time but also the independent spirit with which she faced them. Her art also drew on a language and themes of her own, using her experiences and memories as raw material.

The painter spent two seasons in Paris which would prove crucial to her artistic evolution – the first in late 1923 and the second in 1928. She saw exhibitions by Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse, collaborated sporadically with Sonia Delaunay, and studied the work of Georges Braque and Marie Laurencin, with whom he shared a taste for female portraits.

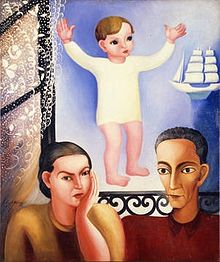

In this context, Sarah Affonso’s work reflects a widespread resurgence of figuration in postwar European art. In her case, it was an intimate and sensitive figuration – an unprecedented approach in Portugal that explored a feminine and family universe and transposed folk art and imagery from her childhood in Minho (Northern Portugal) into a modern, cosmopolitan art.

José-Augusto França’s magnum opus 100 Quadros Portugueses no Século XX(100 Portuguese Paintings in the 20th Century) dedicates a beautiful text to Sarah Affonso’s Sereia (Mermaid, 1939):

“The best thing about this painting, which is inspired by folk religion and the painter’s memories of Minho, is that its protagonist is the naked rosy mermaid, with her golden hair, rather than Our Lady of Salvation! Catholic grace is superseded by the grace of art…”

The text goes on to perfectly outline the painter’s main contribution to coeval Portuguese art and her paradoxical and unique position in it: “Emerging in ‘independent’ showrooms in 1930, the painter brought a breath of fresh, delightful air to exhibition halls… a childlike taste for poetic innocence, in an unusual dimension of modernism which somehow retained its ability to create original objects – all the way (if it were to make history) to the final and synthetic structuring of Almada’s paintings in Lisbon’s maritime stations, six or seven years later – in a chronological logic in which Sarah Affonso, Almada’s wife and colleague, fits without fitting. Which, by the way, is her situation in the Portuguese painting context of her time.”

Sarah Affonso occasionally leaves portraits aside – her work’s most distinctive feature – and opts to include certain aspects of Minho’s folklore in her compositions: traditions and fairs, processions and pilgrimages, along with folk mythologies. These works show that the city of Viana do Castelo has left a mark in her childhood and teenage years, and that Minho’s special character has stayed in her memory.

In 1962, António Pedro highlighted “the delicious originality of this folkloreless painter’s Minho adventure – the Minho I speak of lies in the memory of taste, not in anecdotes, and is therefore a category, not an accident.”

The exhibition at the National Museum of Contemporary Art, along with its catalog, aims to fill this lacuna and publicize the work of one of the most notable Portuguese modernists – a tribute to an artist who, despite all constraints, created a language of her own and knew, in the words of museum director Emília Ferreira, how to be a “skilled weaver” of her time.