entrevista

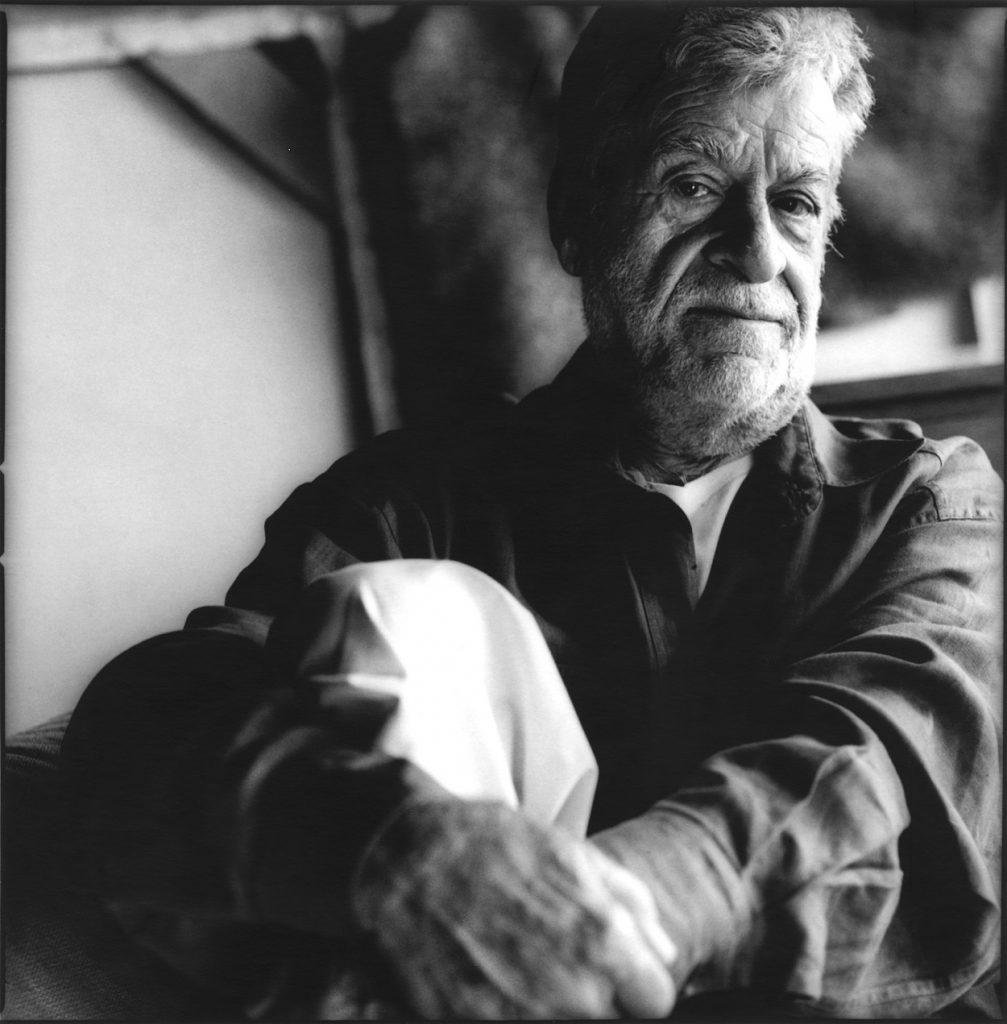

Fernando Lemos

"I understand design as a psychoanalytic study of dreams"

From June 6, MUDE - Museu do Design e da Moda presents at the Cordoaria Nacional - Torreão Poente an important retrospective exhibition of the work of Fernando Lemos in the area of design that also includes works originating from other fields of creation, such as photography and painting. Agenda Cultural de Lisboa spoke with the Portuguese artist, who has resided in Brazil since 1952.

How did you get started in design?

I started graphic work at the age of 15 when I was an industrial lithographer. I attended the School of Decorative Arts António Arroio and dedicated myself professionally to creativity in what concerns the general profession of domestic utilities and techniques of general use. I gradually entered this graphic work and the first works I did, still in Portugal, were visual communication logos that identified companies.

Is that the material that is shown in the Fernando Lemos Designer exhibition?

Yes. The thematic agenda of this exhibition is all about that. This is the first show dedicated specifically to my work as a graphic artist or designer. The idea came from MUDE, and I’m very happy that it’s happening in Lisbon. We have been working on this exhibition since 2017, the year in which the director of MUDE, Barbara Coutinho, invited me. The catalog, which is actually a book, is co-edited by MUDE and Imprensa Nacional – Casa da Moeda. The museum also endorsed a documentary about my work, which is being done by Miguel Gonçalves Mendes and Victor Rocha.

Apart from the exhibition, are there more initiatives concerning your work?

Galeria Ratton and Galeria 111 decided to join this initiative and organize two other exhibitions. Ratton will exhibit my work in tile, for which I made new designs. Galeria 111 shows the latest drawings and watercolors and my photographs from the surrealist era. The Imprensa Nacional – Casa da Moeda will also launch a book of my photographs that includes some unpublished ones.

It is inevitable to ask a question about the Azevedo-Lemos-Vespeira exhibition that in 1952 provoked great controversy and scandal, dragging crowds to Chiado. Can you remember what Lisbon was like at the time?

Our Lisbon had several faces but, in a way, we consideredArmazéns do Chiado the only authentic one. It was a provincial Lisbon, and so it remained for a long time. Our exhibition has, to some extent, breached this Lisbon provincialism, kind of snobbish at the same time, having as an image the poor middle-class pattern of Armazéns do Chiado, where we got inspiration from the manikins themselves and from which we made emblems. But that Lisbon was a difficult place for us because censorship was greater than all that. Art was provided by the SNI (National Information Office) where we had no participation. That is why I considered the Lisbon of those times as the city where the Portuguese were leaving. A city solely with automobiles and offices. A city which the 25th of April came to change. It will be great to return to Lisbon so many years later and feel it very different than from before.

As that reality led you to define yourself as “another Portuguese looking for something better”?

Precisely. I left Portugal in the 50s because I did not want to be one more victim of the fascist dictatorship. I left because I was being chased. The phrase you quoted refers to that time and that reality.

In that exhibition in Chiado you presented a set of photographs, now famous, that through an overlapping technique produced formal surrealism recomposition. How did they come about?

Within the surrealist camp, no one was very interested in using photography. I tried to capture, through a hidden vehicle like photography, the face of the Portuguese people because I thought there was nothing that had shown us the face of our people. The first photographs focused on the faces of my friends within the group.

At this distance, what do you think has been the most important legacy of the surrealist movement?

Surrealism brought joy to a post-war period and had the advantage of being the only territory where dreams spoke the truth. It came about to promote the unveiling of reality. Reality for us does not exist. What exists is what we put into it again everyday. A new trend brought about this unveiling of the concealment that is life and that in some places is a political form of organization to take power. Surrealism seems a lie and it is, as all art is a lie.

In 1952 you decide to leave for Brazil.

I did not come to Brazil to stay. I stayed because I liked it and I adapted. First, I was in Rio de Janeiro and then I settled in São Paulo. In Portugal, freedom was the most difficult thing to get in an authoritarian country where I had felt cloistered since childhood. Here I became free. And it was here that I developed my work as an artist and designer. I did a little bit of everything in terms of graphic design: I created brands, magazine covers, posters, illustrations; in short, everything related to visual communication. I had in São Paulo an industrial design office where I launched a children’s literature publisher, 35mm video collage for marketing and business communication, book covers and posters, films, fabric and tile printing, panels for the metro, exhibitions and commercial spaces, institutional walls for building construction, murals. I drew exhibitions, I did many poetry illustrations and advertisements for various public agencies, tapestries… I also collaborated in ABDI’s foundation—the first Brazilian Industrial Design Association—and I was a teacher and cultural manager. But you know, I kept working from time to time in Portugal. For example, for several years I collaborated with my great friend José-Augusto França in the magazines Arts Colloquium and Letters Colloquium,making illustrations and giving news of culture and arts in Brazil. I remember it was for Colloquium that I wrote a piece about Joaquim Tenreiro. That’s all I’ve been seeing in boxes and crates in my house for the past two years, and it will be displayed in Lisbon at this exhibition, according to the curatorial look of Chico Homem de Melo and the exhibition design of Nuno Gusmão, two graphic designers by training. One Brazilian, the other Portuguese…

What else changed with your going to Brazil?

There was a great change in the sense that I became free, I became someone else. Brazil is a country of creativity. The way they speak is, in itself, creative. This insistence saying it is the same language is not true. In Brazil there is no language, there is communication. It was in Brazil that I learned to distinguish the face of the Portuguese people from that of Brazilians, and this influenced my creative method. Creation does not happen by chance. It happens because of the culture we live in and, here, a lot of people helped me make sense of what I hadn’t understood.

You say that you are always a designer in everything you do. Could you elaborate on that?

I say that because I’m very graphic. I make everything with a graphic vision. I understand design as the psychoanalytic study of dreams. Design is what happens, not just what is thought. Design is not synonymous with drawing. It is an idea that takes the specific shape of the content. It is the intention of an idea.