exhibition

Sorolla, that illustrious stranger

'Tierra Adentro - The Spain of Joaquín Sorolla' at the MNAA

Until the end of March, the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga exhibits 118 paintings by Valencian artist Joaquin Sorolla, the greatest figure in modern European painting. Organized in partnership with the Sorolla Museum in Madrid, the exhibition aims to discover an artist very little known in Portugal, although in recent years he has been recognized in the painting of the late nineteenth century and beginnings of the 20th century. At the heart of the landscape, Tierra Adentro - The Spain of Joaquín Sorolla reveals, against all stereotypes, a "modern" painter in search of a republican, regionalist and regenerationist Spain.

Seaside scenes on Levante beaches, fishermen in the coastal area of Valencia or children and young people in summer jousting are some of the most striking images of the work of Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (Valencia, 1863 – Cercedilla, 1923). In part, those are the ones which earned him fame and popularity in life, but also a notorious indifference, and even historical and critical irrelevance, for decades. In Portugal, as António Filipe Pimentel and José Alberto Seabra Carvalho point out in the review included in the catalog of the present exhibition, Sorolla was practically ignored by the historiography of the art, having been the object of “a simplistic and stereotyped interpretation of his work to the point that many understood him as a kind of Spanish Malhoa. ”

The director and the deputy director of Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (MNAA) consider that the Valencian was “a great painter, modern in his time although not ‘avant-garde,’ innovative but committed to the masters of the past.” For this reason, he is essential for the understanding of “the finissecular painting of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century, without obeying the official and academic narratives that, so to speak, move from Impressionism and Post Impressionism to Cubism or Modernism as if between them there had been nothing but a desert.”

The commissioner of Terra Adentro – Spain of Joaquín Sorolla, Carmen Pena, explicitly explains, as a cause for so many misunderstandings and prejudices regarding the work of “luminaries” such as Sorolla, the fact that the art historiography of the last century privileged the Impressionists, “considered avant-garde painters of the nineteenth century.” After all, it was these “contemporaries” that held “a hegemonic role in this narrative, which privileged avant-garde phenomena as an explanatory process of contemporary art.”

Not being therefore avant-gardist, what is so “modern” in Sorolla’s work, and how did the painter recover a prominent place internationally in the historiography of art (a place which the Spaniards never refused him)? Carmen Pena justifies this with the “officialization” of the avant-gardes, who went from “transgressors to canonical models,” and with this helped to highlight in the art history of the last century some of these so-called “modern integrated”, that is, painters “of their time,” trained in the national schools, including Sorolla, who made frisson at the great halls of Paris and at the universal exhibitions.

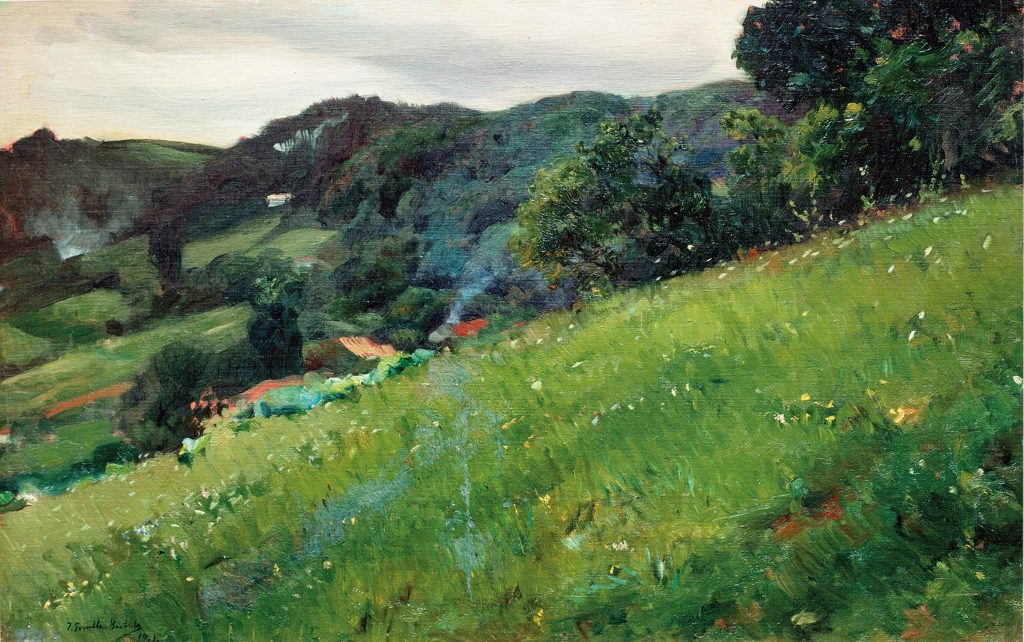

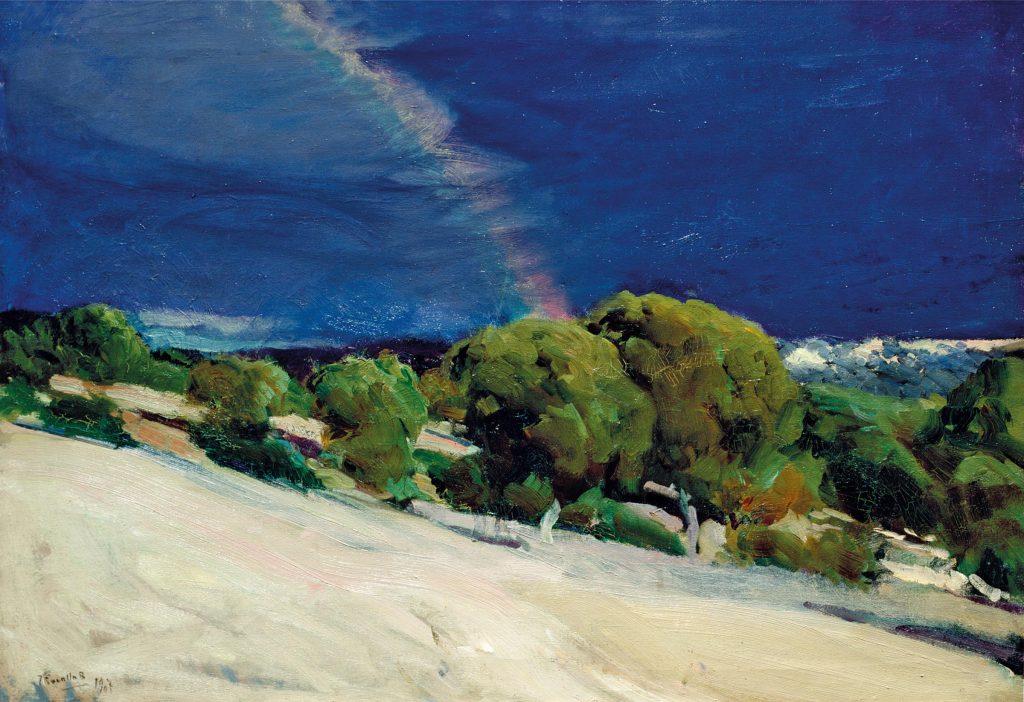

The “modern” in the work of the Valencian painter is emphasized in what Pena considers the “common denominator of his work”: “to capture the endless and changing effects of light outdoors in the context of modern color physics and as an experimental application” and thereby “to achieve modern light effects” which will not be at all strange to the “new” art of photography to which he was particularly attentive. Indeed, just as his luminist and Impressionist contemporaries, like Degas or Monet, in landscape painting.

It is precisely the other Sorolla, the “introspective” one, the one from Terra Adentro, as if contrasting with the “solar” Sorolla of the Mediterranean beaches, that affirms the genius of a “modern”. According to Román Casares, of the Museo Sorolla Foundation, it was “in the Spanish landscapes of the interior, sometimes naked, severe, imposing” that the painter discovered “other reasons for his paintings and other reasons to perceive his country.”

In this magnificent exhibition of the MNAA, the visitor can witness the two sides of Sorolla: that of the “optimistic and luminous” realist whom so many know; and the one that still remains almost unknown – that of the solitary landscapes of a dreamed Spain, demonstrating, as Carmen Pena points out, the “Spanish regenerative thought of its time” which sought through painting new “identity icons.” The latter was, of course, a great revelation.