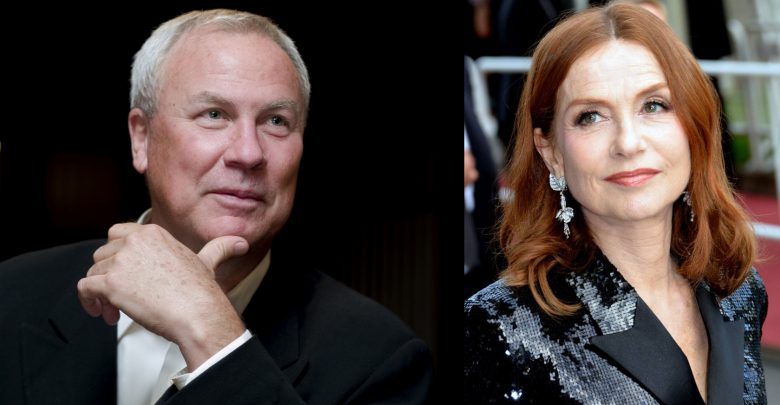

With a world premiere scheduled for the Espace Cardin in Paris on May 22 of Mary Said What She Said It’s a monologue written by the African-American writer Darryl Pinckney, a recognized author in the theater world for his collaborations with Robert Wilson. In fact, this is an even broader reunion, since the acclaimed French actress Isabelle Huppert will join them more than 20 years after this “glorious” trio brought another monologue to the stage: Orlando, from the Virginia Woolf novel.

As Pinckney himself points out, “the ever inventive Robert Wilson offers to the great Isabelle Huppert the throne of Queen Mary of Scotland, the monarch who, because of her passions, lost her crown.” A three-act play, Mary Said What She Said It’s a story of love, power, and betrayal of a woman who exemplified the irrepressible desire for freedom. Huppert’s talent, therefore, is to be measured to the full extent of her talents.

In a production at the Theater de la Ville (directed by Luso-French Emmanuel Demarcy-Mota), not only does Wilson shine on stage, but the show’s stage set and lighting does as well. It also features original music by the famous composer Ludovico Einaudi and costumes by Jacques Reynaud.

The show is part of the 36th edition of the Almada Festival that runs from July 4 to 18 in Almada and Lisbon. The tickets, as well as the signatures that give access to all the shows at the festival, will go on sale later this month.

“It was not intended as a retrospective, nor did we try to showcase João Onofre’s entire work,” says Delfim Sardo, the curator of Once in a Lifetime [repeat]– an exhibition that brings to Culturgest some of the most significant works of the Lisbon-born artist (1976). One could say that, throughout the exhibition, “the focus is on this limbo of sorts between Romanticism and art history’s major themes, especially love, failure or death, which seems to permeate Onofre’s entire work… All this with undeniable irony.”

The exhibition begins on the outside, at the entrance to Culturgest, with Box, a 1.83m steel cube that hints ata grave’sstandard depth of 6 feet. The piece is a quote of a seminal minimalist sculpture – Tony Smith’s Die (1962) – which Onofre revisits as a soundproof box in which a death metal band (Holocausto Canibal) delivers “an extreme performance”: imprisoned inside, the band plays until the oxygen runs out (the performance will take place again on May 17 at 10.30 pm).

The trilogy O Estúdio [The Studio]also echoes modern and contemporary art history. The three videos are a direct quote of Bruce Nauman, an influential US conceptual artist who used his own studio as the focus of some of his most remarkable works. Nauman believed that “art is what the artist does in his studio,” and Onofre seems to take inspiration from this motto to film – “with a trenchant irony regarding the transfiguring ambition of artistic images” – a female singer performing Sol LeWitt’s ‘conceptual art’ prepositions to the melody of Madonna’s Like A Virgin ; to have an illusionist performing the traditional levitation trick with his partner (again, a Nauman quote); and to release, in the studio itself, a vulture which ends up destroying everything – an ironic take, as the curator points out, on the “necrophagy of the artist’s work.”

Another reference to Nauman, more specifically to his famous Self-Portrait as a Fountain, emerges in Untitled (Luminous Fountain), a self-portrait against the backdrop of Praça do Império’s Luminous Fountain in Belém.

Movies are another source of quotes in Onofre’s career. If, on the one hand, the oldest work in this exhibition is a short excerpt from Antonioni’s masterpiece The Eclipse– a looped sequence in which the main characters (Alain Delon and Monica Vitti) play out the seduction game with their hands -,the most recent (and until now unseen) piece consists of a complex two-and-a-half-hour single shot, recalling Godard’s One Plus Oneor Aleksandr Sokurov’s The Russian Ark.

Untitled (zoetrope) is an extremely long take starring a gospel choir,a music quartet and a mixed rugby team, who “stage an endless ritual, to the point of complete exhaustion.” To the sound of I want to know what love is– a pop tune that topped the charts in the 1980s – the rugby players try, one by one, to sing the song’s chorus to a microphone in the middle of the set, surrounded by the musicians and the choir. But they can never finish it, because they are repeatedly tackled by their teammates.

This filmed performance is particularly illustrative of the spirit behind the entire exhibition, which was conceived, as Delfim Sardo points out, “around the importance of circularity and repetition as a creative process” And there is also “the ubiquitousness of the idea of finitude, of lack, failure and error, which are intrinsic to life and, therefore, to artistic creation.” Yet in João Onofre’s work, these experiences are seen through the lens of “an exquisite irony,” making each piece “oscillate between tragedy, comedy and concept.”

Addressing the audience, André Amálio begins by promising a different show from all those he has directed before. “This one is not political. This one is about love,” he says. Then, each of the actors explains how they will express love on stage and announce “their love” – a father, in Júlio Mesquita’s case, or a partner, in Amálio’s case. All this because, to paraphrase Slovenian philosopher Srecko Horvat, “love is revolution.” Always, and in all circumstances, “our revolution.”

But “revolution” is a political concept, isn’t it? “This is a false premise we have decided to adopt, because what we really want is to suggest that all love is political,” Amálio says. Political because, he believes, “all love stories” are political.

It is precisely in this sense that Amores Pós-Coloniais (free translation: Postcolonial Sweethearts) draws from interviews with Colonial War soldiers who had children with black African women during the conflict, followed by memories of white Portuguese women who experienced love stories with African activists (such as Agostinho Neto and Amílcar Cabral) and testimonies of children born from interracial relationships.

However, the patchwork Amálio and his creative/love partner Tereza Havlíčková build goes even further. The overseas empire has fallen and we have been living, since the end of the fascist regime, in a postcolonial society, although thought and behavior are still colonized. It is particularly interesting to listen to the play’s contemporary testimonies, especially those of the black actors (Júlio Mesquita, Laurinda Chiungue and Romi Anauel), all born after the 1974 revolution but still marked by a nefarious 500-year heritage we stubbornly try to hide. After all, Amálio asks us, “what is the most decisive event in the history of this country: the discovery of the maritime route to India or the beginning of colonialism and transatlantic slave trade?”

If, on the one hand, Amores Pós-Coloniais is an openly militant and political indictment, it is also, on the other hand, a show about love. In spite of all the seriousness that hangs in the air when these topics are addressed, it is also a festive experience complemented by music, dance and food. So let us celebrate love – “our revolution,” as the show says at some point. For, as the play implicitly suggests, only love can finish the incomplete decolonization process. Here in Portugal, right now, in 2019.

How did Fado come into your life?

It runs in the family, I have Fado blood running in my veins. I usually say that I don’t even know when it started, because I’ve been going to Fado houses since I was three. I remember listening to Fado records at my aunt’s house, the Fado singer Joana Correia, when I was six or seven. At the age of eight or nine, I started writing the lyrics in a notebook to memorize what my aunt was singing. When I was 13, I participated in the Great Night of Fado contest. I won, and that’s when I was sure that this was what I wanted for my life.

Was your participation in the Great Night of Fado contest a turning point?

People around me have always encouraged me to go on, but yes, that’s when the penny dropped.I knew that was what I really wanted.

You often compare Fado houses with the ritual of going to Mass…

A self-respecting Fado singer must go to Fado houses because that’s where Fado really happens. That’s where we engage with more experienced Fado singers, where we get the inspiration we need when we take to the stage. Moreover, they have a more intimate ambiance, we are closer to the audience. I love being on stage, that’s where I feel like myself. I’m a very anxious person, but when I get on stage my anxiety disappears.

Your debut album has earned a lot of praise from critics. Were you expecting such a warm reaction?

I was sort of expecting good reviews, because I know the work I did. I spent three years working on that album. My goal was to make this album exactly the way it came out, and to send a message to people from my generation who do not listen to Fado. I feel that young people who are now starting their Fado careers have also learned a lot from me, and that’s awesome. That’s what I always wanted, to be considered an influence. I’m only 25 years old, although many people think I’m older…

Do you think this has something to do with the motion that Fado is for older people?

People don’t know what the essence of Fado is, they don’t know it… It’s important that people in this circle, like myself, show some of the history. There is a great deal of ignorance regarding the history of Fado. I often say it wasn’t me who chose to sing Fado, it was Fado that chose me – this is evident in my path. I love singing, but my main goal was to send a message, to trigger people’s curiosity: learn more about Fado because there’s a lot to learn!

Does the fact that Fado is basically a genre with a tradition and an associated ritual drive younger generations away?

I think that distance is due to the image Fado has always had. The black, somber clothes, the long dresses, the sad lyrics… I remember being a girl and some people telling me this kind of music was not suitable for my age. Nowadays, Fado has a much lighter image. The lyrics are more modern, and Fado singers sport a different look… This was a necessary change, but there are lots of traditional elements that should be maintained. I don’t think clothing defines a Fado singer or any other singer. I don’t really care if someone sings in a skirt or in a pair of pants, but there’s a certain degree of thoughtfulness one must have. Each person must have their own identity and their own taste. Fado is in the voice, not in the clothes.

This album features Diogo Clemente and Ângelo Freire, two Fado heavyweights. How did this collaboration come about?

We’ve known each other for a long time, and they kept telling me that when the time came, they would want to make a record with me. I grew up with them by my side. At some point I felt the need to leave something of my own, a record. I think it takes a certain maturity and some experience, not only in Fado but in music in general. You need to have a story to tell other people. I’m 25 years old, I have my whole life ahead of me, but I felt I was ready to make a record. I already have 15 years’ experience in Fado, it was the right time. I mentioned this to Diogo and he also thought the time had come.

You decided to name your first album after yourself. Why?

First of all, because I wanted to present myself as Sara Correia. Then, because these traditional fados are almost like my autobiographies, my life stories. I thought it didn’t make sense to try to find a motto for this album. I am the motto, Sara Correia, just the way I am.

Being compared to Amália is the biggest compliment you can get?

Yes, but it’s also a great responsibility. I don’t like comparisons. I have my idols, just like anyone else. For me, Amália Rodrigues is the essence of Fado, its greatest exponent, I’ve been singing her songs since always. I even recorded a version of Fado Português, which I was hesitant about.

Were you afraid?

I was, because some songs you just can’t improve. What Amália did is perfect, which puts the bar really high. But I thought, ‘Why not?’. I’ve also recorded songs from other Fado singers I admire a lot.

You will showcase this album at Capitólio on February 21. Tell us more about this show.

I’ll be doing new things, I’m preparing a few surprises, but it’s all about singing Fado, of course, because that’s what I know how to do.

What will the future bring?

Right now I’m focused on this album, but I already have some ideas for the next one, because the show must go on… Now I’m focused on promoting this album and giving concerts. I have some concerts scheduled, I’ll perform at Alfama Box again and I’ll be in Norway and Vienna soon… It’s funny how much audiences abroad love Fado. Even though they don’t understand the words, they always ask for the most traditional songs, the most ‘hardcore’ fado.

What is the dream concert hall for a Fado singer?

I have many dreams, but none about a concert hall. My dream is to sing on stage, wherever it is, and whoever the audience is. That’s my dream, being able to sing for other people. Meeting other artists, other musical cultures.

You graduated in sculpture but devoted your life to singing. Looking for an analogy, could we say that opera is like carving out a character on stage through singing and acting?

Yes, we could. It’s also a creative act. Within acting we have an enormous amount of creativity to explore. If there’s something I’ve learned from my past in sculpture and my years in Fine Arts was to create enough tools to feed the imagination which is necessary for opera and concerts. Especially in concerts, because in opera we have a context that helps us, whereas in concerts we’re on our own. We need images and experiences to feed that imagination, and Fine Arts have given me that repertoire of images which is so important for providing context, for putting myself in the shoes of the ‘other’. Basically, for understanding the ‘other’ and myself as well.

Do people still tend to value opera singers for their vocal qualities rather than their dramatic talent?

Since quite a few years ago, opera stage directors have been playing a greater role in choosing the cast, and singers are now required to have, in addition to the voice, a strong stage presence and know how to embody the characters. Directors have a great deal of power in finding someone who is cut out for the role, and sometimes they are even willing to make some musical concessions in favor of their character idea.

You have specialized in the Baroque repertoire. Why?

Aesthetically, it is the repertoire with which I identify the most. When I started listening to classical music, I listened to Bach, Haendel. But there was also a chance element, because I started my career with Baroque orchestras and I became more enthusiastic about the repertoire. And there are so many things that have never been done before, so much to be discovered in Baroque music. And starting from an almost virgin repertoire allows for greater creativity, less burdened with references. The Baroque repertoire offers a freedom that cannot be found in other styles, and I like the task of completing an unfinished score, one that gives us room to choose an approach and even select the instruments we play.

In the preface to Alceste, Gluck wanted to reform opera by turning it into a true musical drama. What did this renewal consist of?

It was about composing music in accordance with poetry, with the text. Without resorting to artifice, breaking away from some of the Baroque repertoire’s predictable structures and from some indulgence and virtuosity on the part of singers. Gluck wanted to abolish excesses in favor of a pure approach that would cut straight to emotions. Singing Gluck requires a purity of the vocal line and a lyricism which the Baroque repertoire doesn’t have.

Tell us about Alceste, the character you will play. How would you define her?

Alceste is a woman who sacrifices herself for her husband. Because of the weight of Alceste interpretations in the 1950s and 1960s, I had imagined a determined and strong heroine who exalts her courage and takes her fate in her own hands. But when I started reading the libretto, I realized that the character is more than a rigid statue. I perceive her as an anti-heroine. Someone who is not a heroine by nature, but who does what she must and believes she is right. She chooses to sacrifice herself as the last resort. After all – and this is very clear in the score -, she is a character who is always wavering between fear and courage. This is what humanizes her and pushes her forward. Deep down, she is a character with a certain fragility, despite all her strength and determination.

What challenges does this role present?

It’s a very tense role. This is an emotionally strong character, and the challenge is to find the perfect balance between acting and singing.

You have played Despina and said you would like to play Mozart’s Suzana. These are light roles that require great liveliness. Do they reflect to another facet of your personality?

Yes. Although I feel very close to Alceste and my personality allows me to approach this kind of drama, I have always played agile, lively, spicy, young roles. These are the roles I usually get. Alceste is not the kind of role I have the opportunity to play every day.

What would you highlight in this new staging by Graham Vick?

The way he biulds the character. I was persuaded to play the role because he believed I could do it, which is not evident for my kind of voice. His idea of Alceste as someone who is not necessarily strong, with a fragile and vulnerable side, is what interests me the most, and it coincides with my own vision.

How would you convince someone who has never been to the opera to come see Alceste?

To watch an opera you must be willing to accept this type of language. And in the case of Alceste, to accept the experience of coexisting with a theatrically powerful character. Then you need curiosity, because sacrifice is not a very common subject from this perspective. But Gluck’s music cuts straight to emotions, which makes this a very moving opera. At the end of the day, this is what we expect when we go to a show – to feel and experience emotions. This is, in and of itself, a valid reason to come and see this Alceste..

LOUIE LOUIE (Escadinhas do Santo Espírito da Pedreira 3)

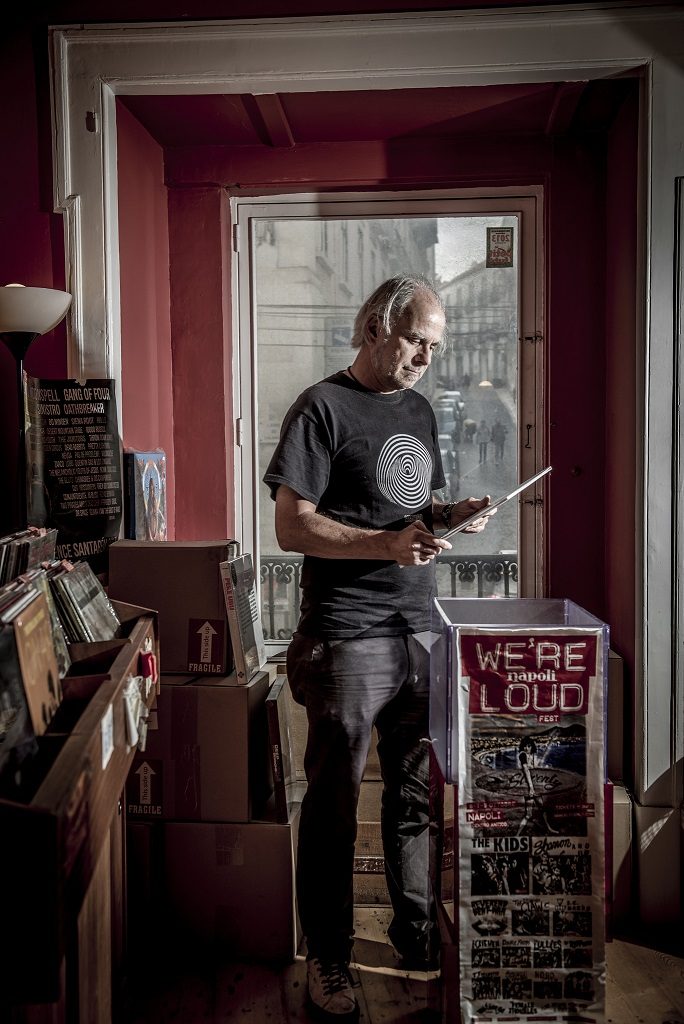

The Lisbon store opened in 2007. But the Louie Louie already existed in Porto. Jorge Dias was a partner in this store and also had a share in Carbono. Louie Louie is considered an alternative to megastores. Vinyl became a salvation for this kind of stores. The substantial increase in tourism in Lisbon as well. Foreigners buy more, even if in amounts that take into account the return journey. Jorge Dias distinguishes three types of customers: the ones who only buy new discs, the ones who only buy used ones, and the ones that look for a particular disc and don’t care if it is new or used. As we talked, Homogenic by Björk and the first album of Caetano Veloso played in the store. From the music released in 2018, the store recommends Thom Yorke’s soundtrack for the remake of Suspiria and the easy going surf-pop of Khruangbin (Com Todo el Mundo).

FLUR (Avenida Infante D. Henrique, Armazém B, loja 4)

Flur exists since 2001 and maintains the same address near the Lux Frágil nightclub. The store values the familiarity it has created with its customers who never traded purchasing records at Flur for online shopping. Flur also has a website that works mainly as a storefront and that, along with the weekly newsletter, is the only promotion they make. Vinyl record sales represent twice the amount of CD sales. New ones also cost roughly twice as much. The music being played in the store at that moment belonged to the album Izlamic Songs, by Muslimgauze. When choosing important albums released in 2018, Zé Moura, manager of Flur, referred the album Belzebu, by Telectu, and Taipei Disco, with exclusives by the DWART project, both from the Holuzam label, a very recent publisher owned by Flur’s three current partners.

VINIL EXPERIENCE (Rua do Loreto 65)

The place matches the description of a mezzanine: “a floor, usually with low-ceiling, located between the store or ground floor and the first floor.” In practice it is as if José João (Jota) received us in a room in his own house. The records are somewhat organized but it is certain that only the manager can locate a specific record. They are closed two days a week (Tuesdays and Wednesdays), as well as on Sundays. During the conversation, we listened to a Jimi Hendrix tribute band, The Purple Fox, and the modern psychedelic band King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard. Jota also feathered his own nest when choosing a recent record that left a mark on him: it was the EP 909DemocrashDrug by Portuguese band Democrash, which is a shared edition by Raging Planet and Vinil Experience.

GLAM-O-RAMA (Rua do Viriato 12)

Glam-O-Rama was Luís Lamelas’ gateway to Lisbon. 4 years ago that became reality. A short time ago, he was able to negotiate a realistic rent value with the owner and Glam-O-Rama moved to where VGM once was. The store also promotes record presentations, autograph sessions and acoustic concerts. We talked to him as he was starting to work and the store was silent. Moments later, the instrumental surf-rock of Head Shrinkin ‘Fun by The Bomboras could be heard. Glam-O-Rama’s profits approximately the same from CD and vinyl; used CDs are gaining some ground because they are cheaper. The conversation ends with the re-edition of the album A Wind of Knives by Zygote, an important record among the many that Luís Lamelas has recently heard.

CARBONO (Rua do Telhal 6B)

Carbono was the first used record store to emerge in Portugal, in 1993. What immediately impresses those who enter Rua do Telhal’s place is its size. We can walk around at will although we are surrounded by records at each corner and in the center of the store. And there is more material to see and buy on the ground floor. According to the person in charge of Carbono, vinyl has come into fashion. Individuals who keep good editions do not want to sell them and the market is increasingly full of re-editions that do not have the same value. He also tells us that all stores normally sell more CDs than vinyl. The price is a decisive factor. The music that was heard belonged to the “bootleg” With your host Bob Dylan 2007/2008. The 2018 album that João Moreira chose for us was Knock Knock, by DJ Koze.

TABATÔ (Rua Andrade 8A)

To get in the Crew Hassan Cooperative you have to descend a few steps and then you are at Tabatô. The man responsible is Frenchman Bastien who visited Portugal in 2010, to do some work as a DJ (world music, reggae), and came back to stay. The store opened in 2015. Customers are looking for rare records, African music from the PALOP (African countries with Portuguese as their official language), and receives many people from France, Germany and the Netherlands. Tabatô closes on weekends and this may explain why Mondays and Fridays are the days of greatest affluence. When we spoke with Bastien the store was minutes away from opening and music came from upstairs, where a radio played The War on Drugs. Bastien chose for us, amongst his most recent discoveries, the albums The Rule of Fire, by Luís Cília, and the very rare maxi-single from Cape Verdean Cruz Pinto (funaná).

DISCOLECÇÃO (Calçada do Duque 53)

After staying in three other spaces of the city, the Discolecção is now at Calçada do Duque. The space was full. We listened at a good volume to The Bracknell Connection, by Stan Tracey Octet, British jazz of the 1970s. Vítor has always had exclusively vinyl, but now we can find in a noble area of Discolecção dozens of CDs that in no way diverge from the general criterion. It is increasingly difficult to find material of this quality from individuals. Vítor continues to attend the Utrecht fair, stating that it’s the biggest and most important one for this market. He relies on the displayed items, the surprise effect and the ability to bring past recollections to those who pass by and purchase. He chooses from the most recent things that surprised him, A Meditation Mass (1974) by the German group Yatha Sidra, and Your Daily Gift (1971) by the Danes Savage Rose. Both in the genre that Vítor Nunes most appreciates, classic rock and its variants.

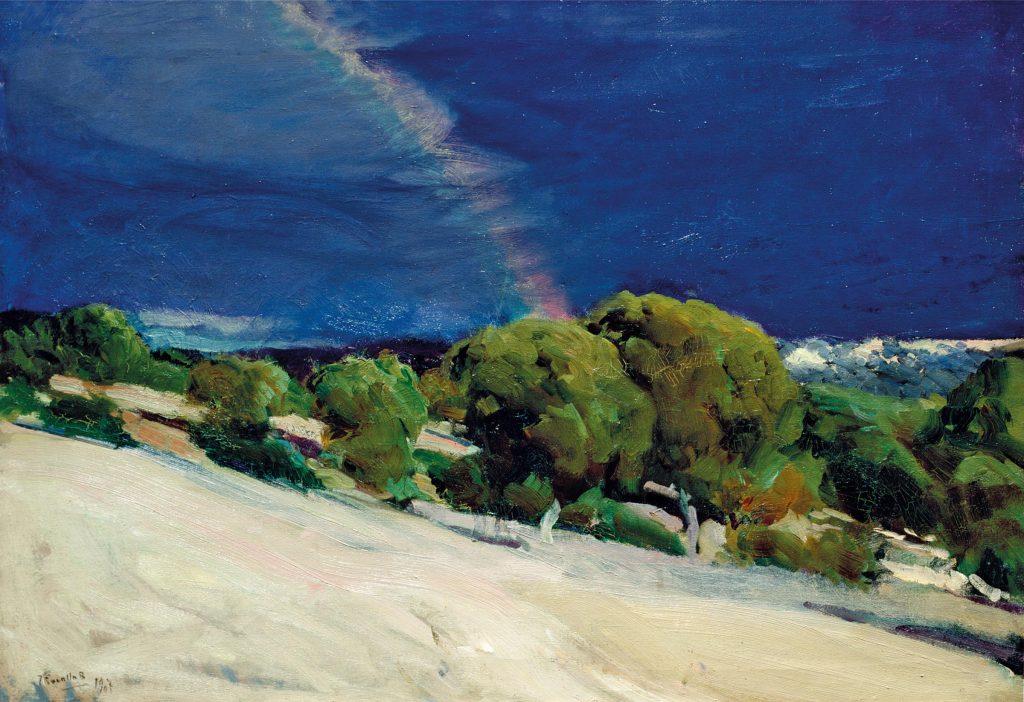

Seaside scenes on Levante beaches, fishermen in the coastal area of Valencia or children and young people in summer jousting are some of the most striking images of the work of Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (Valencia, 1863 – Cercedilla, 1923). In part, those are the ones which earned him fame and popularity in life, but also a notorious indifference, and even historical and critical irrelevance, for decades. In Portugal, as António Filipe Pimentel and José Alberto Seabra Carvalho point out in the review included in the catalog of the present exhibition, Sorolla was practically ignored by the historiography of the art, having been the object of “a simplistic and stereotyped interpretation of his work to the point that many understood him as a kind of Spanish Malhoa. ”

The director and the deputy director of Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (MNAA) consider that the Valencian was “a great painter, modern in his time although not ‘avant-garde,’ innovative but committed to the masters of the past.” For this reason, he is essential for the understanding of “the finissecular painting of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century, without obeying the official and academic narratives that, so to speak, move from Impressionism and Post Impressionism to Cubism or Modernism as if between them there had been nothing but a desert.”

The commissioner of Terra Adentro – Spain of Joaquín Sorolla, Carmen Pena, explicitly explains, as a cause for so many misunderstandings and prejudices regarding the work of “luminaries” such as Sorolla, the fact that the art historiography of the last century privileged the Impressionists, “considered avant-garde painters of the nineteenth century.” After all, it was these “contemporaries” that held “a hegemonic role in this narrative, which privileged avant-garde phenomena as an explanatory process of contemporary art.”

Not being therefore avant-gardist, what is so “modern” in Sorolla’s work, and how did the painter recover a prominent place internationally in the historiography of art (a place which the Spaniards never refused him)? Carmen Pena justifies this with the “officialization” of the avant-gardes, who went from “transgressors to canonical models,” and with this helped to highlight in the art history of the last century some of these so-called “modern integrated”, that is, painters “of their time,” trained in the national schools, including Sorolla, who made frisson at the great halls of Paris and at the universal exhibitions.

The “modern” in the work of the Valencian painter is emphasized in what Pena considers the “common denominator of his work”: “to capture the endless and changing effects of light outdoors in the context of modern color physics and as an experimental application” and thereby “to achieve modern light effects” which will not be at all strange to the “new” art of photography to which he was particularly attentive. Indeed, just as his luminist and Impressionist contemporaries, like Degas or Monet, in landscape painting.

It is precisely the other Sorolla, the “introspective” one, the one from Terra Adentro, as if contrasting with the “solar” Sorolla of the Mediterranean beaches, that affirms the genius of a “modern”. According to Román Casares, of the Museo Sorolla Foundation, it was “in the Spanish landscapes of the interior, sometimes naked, severe, imposing” that the painter discovered “other reasons for his paintings and other reasons to perceive his country.”

In this magnificent exhibition of the MNAA, the visitor can witness the two sides of Sorolla: that of the “optimistic and luminous” realist whom so many know; and the one that still remains almost unknown – that of the solitary landscapes of a dreamed Spain, demonstrating, as Carmen Pena points out, the “Spanish regenerative thought of its time” which sought through painting new “identity icons.” The latter was, of course, a great revelation.

The 50-hectare zone where Parque das Nações is located today and which runs along the river for five kilometers was, at the end of the 1980s, a field of containers, slaughterhouses and polluting industries, where nearby homes were decadent, poor and unhealthy. In 20 years, much has changed in this eastern part of the city, especially in the preparation phase for Expo’98. At the end of the world exhibition, there was concern that the equipment of the venue had later use, in order to avoid its abandonment and degradation. At the same time, large public contracts were launched, such as the Vasco da Gama Bridge, a rail interface and a new metro line with seven stations. This area has become one of the most modern districts of the city, bringing together commercial, cultural and leisure areas and attracting many companies and institutions, all with a privileged view over the Tagus.

The Oriente Station, bold construction of Santiago Calatrava marks the starting point of this itinerary. With a steel based structure, it is often compared to a Gothic cathedral, but breaks with the medieval tradition of the horizontal design of the clasp line. In his creation, the Spanish architect took advantage of tradition and modernization as a bridge between the past and the future, and on the upper platform, Calatrava used the iconography of the tree related to the hills of Lisbon. The structure, which won the Brunel Prize in 1998, accommodates one of Lisbon’s most important railway and bus stations, a metro station (Oriente) and a shopping area.

With its back to Estação do Oriente, at the intersection of D. João II Avenue and Avenida do Pacífico, stands the Vodafone building, by Alexandre Burmester and José Carlos Gonçalves. Primo Valmor 2005, this construction develops at the fenestration level, a contemporary reinterpretation of some themes of the Renaissance architecture, and it is possible to establish an analogy between it and the Casa dos Bicos. It has two distinct faces, one open to the river and another to the avenue, and has a construction area of approximately 70 thousand square meters. It is a building with great urban impact, both for its size and architectural value, and for the technological challenges involved.

In the background, you can see the Pavilion of Portugal, by Álvaro Siza Vieira and now belongs to Lisbon’s University, responsible for its maintenance. It is a building composed of two separate bodies, one of which corresponds to the building – a solid and sober volume – and the other corresponds to a large square covered by an imposing and gigantic concrete palette. The one that is a prodigious work of engineering, is based on the idea of a sheet of paper placed on two bricks.

In the background, you can see the Pavilion of Portugal, by Álvaro Siza Vieira and now belongs to Lisbon’s University, responsible for its maintenance. It is a building composed of two separate bodies, one of which corresponds to the building – a solid and sober volume – and the other corresponds to a large square covered by an imposing and gigantic concrete palette. The one that is a prodigious work of engineering, is based on the idea of a sheet of paper placed on two bricks.

From there, you can still see the Towers of São Rafael and São Gabriel, housing buildings with 110 meters of height of José Quintela. The architecture is visibly inspired by the simplicity and elegance of a boat’s bow towards the river. At the top, two candles appear.

From there, you can still see the Towers of São Rafael and São Gabriel, housing buildings with 110 meters of height of José Quintela. The architecture is visibly inspired by the simplicity and elegance of a boat’s bow towards the river. At the top, two candles appear.

Following D. João II Avenue, next to the Vasco da Gama Shopping Center and at the intersection with Avenida do Índico, the Atelier ARX, by architects Nuno and José Mateus. Intended for offices, commerce and parking, this construction consists of an absolute black granite box softened. It has a unique and contemporary identity and a bio-climatic conception. This box is perforated in the corners, opening over the envelope and emitting audiovisual contents to the outside.

Following D. João II Avenue, next to the Vasco da Gama Shopping Center and at the intersection with Avenida do Índico, the Atelier ARX, by architects Nuno and José Mateus. Intended for offices, commerce and parking, this construction consists of an absolute black granite box softened. It has a unique and contemporary identity and a bio-climatic conception. This box is perforated in the corners, opening over the envelope and emitting audiovisual contents to the outside.

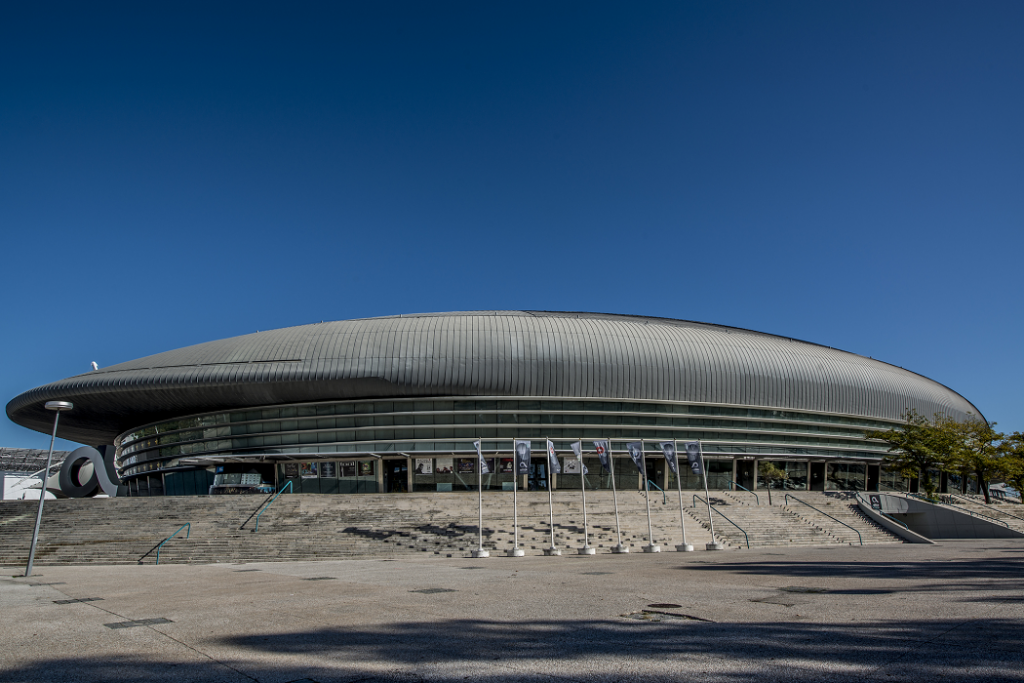

In the background, the Altice Arena, of Regino Cruz, nowadays one of the main halls of spectacles of the country, and that during these 20 years, has hosted several initiatives such as the Web Summit and the Summit of the Nato.

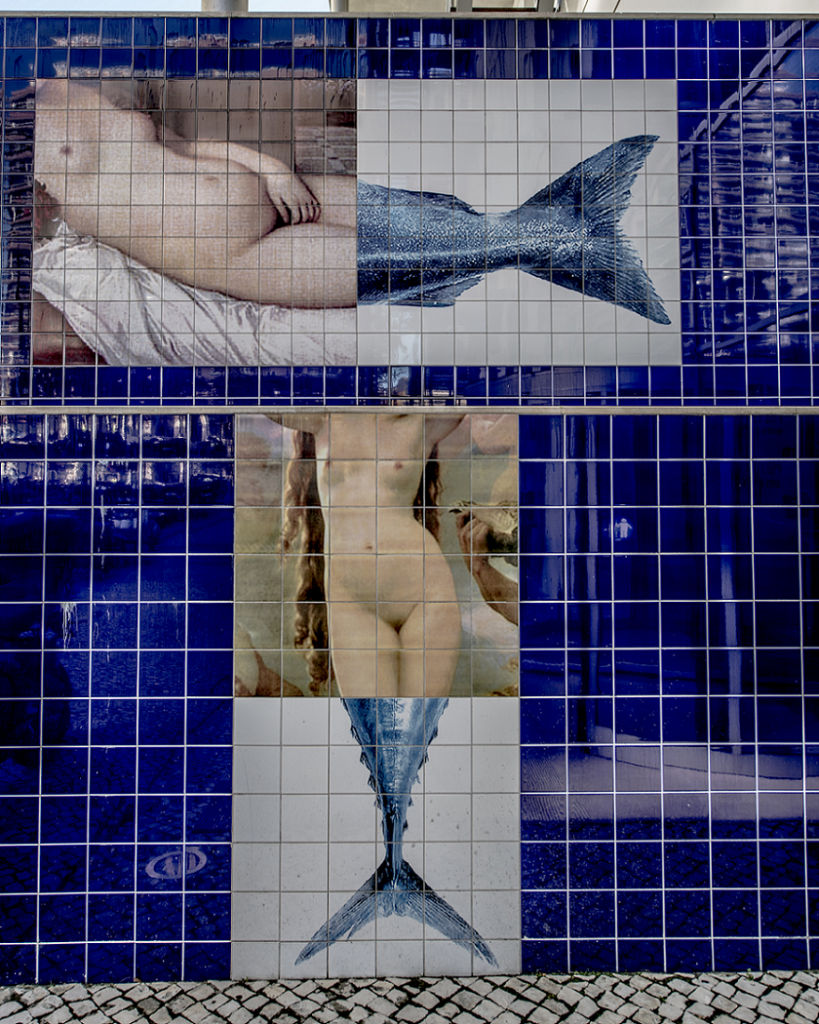

Continuing on Avenida D. João II, around the NOS building there are six tile panels by Leonel Moura who portray mermaids, drawing inspiration from Western painting, more concretely in classics of female nudes. After choosing the nude images he wanted, given his position, he clipped the fish tail through a digital collage. To complete the work, the artist uses the excerpt mermaids singing, from the epic poem Odyssey, from Homer, to the panel on the left side.

Continuing on Avenida D. João II, around the NOS building there are six tile panels by Leonel Moura who portray mermaids, drawing inspiration from Western painting, more concretely in classics of female nudes. After choosing the nude images he wanted, given his position, he clipped the fish tail through a digital collage. To complete the work, the artist uses the excerpt mermaids singing, from the epic poem Odyssey, from Homer, to the panel on the left side.

After crossing the avenue, it is time to stop in front of the VIP Executive Art’s Hotel by Frederico Valsassina, Primo Valmor 2004, to appreciate the tile panel of Erró. In this panel Pop Art, the Icelandic artist represents characters from North American comics and science fiction. Erró, Roy Lichtenstein’s last living disciple, ceded the copyright to this panel to the Viúva Lamego Factory.

After crossing the avenue, it is time to stop in front of the VIP Executive Art’s Hotel by Frederico Valsassina, Primo Valmor 2004, to appreciate the tile panel of Erró. In this panel Pop Art, the Icelandic artist represents characters from North American comics and science fiction. Erró, Roy Lichtenstein’s last living disciple, ceded the copyright to this panel to the Viúva Lamego Factory.

At the roundabout, go down the Avenida da Boa Esperança where, on the left, buildings of Tomás Taveira, the leading representative of postmodern architecture in Portugal.

At the roundabout, go down the Avenida da Boa Esperança where, on the left, buildings of Tomás Taveira, the leading representative of postmodern architecture in Portugal.

Continuing down the avenue, you come to the Vasco da Gama Tower, recently transformed into a hotel by the architect Nuno Leónidas, whose structure symbolizes two candles that embrace the tower.

Continuing down the avenue, you come to the Vasco da Gama Tower, recently transformed into a hotel by the architect Nuno Leónidas, whose structure symbolizes two candles that embrace the tower.

On the left side you will find Italic, a sculpture of Amy Yoes painted in iron, reminiscent of a gigantic typographic character or the three-dimensionality of a capitol of a medieval codex evoking the Portuguese baroque vocabulary. It is possible to enter the sculpture, to surround it and to try to climb it, which allows to gain, with each movement, different internal perspectives and new exterior frameworks.

On the left side you will find Italic, a sculpture of Amy Yoes painted in iron, reminiscent of a gigantic typographic character or the three-dimensionality of a capitol of a medieval codex evoking the Portuguese baroque vocabulary. It is possible to enter the sculpture, to surround it and to try to climb it, which allows to gain, with each movement, different internal perspectives and new exterior frameworks.

Immediately behind, it is discovered There are waters, a panel of tiles specially designed for the Expo’98 by the Chilean artist Roberto Matta, last exponent of the surrealist generation.

Immediately behind, it is discovered There are waters, a panel of tiles specially designed for the Expo’98 by the Chilean artist Roberto Matta, last exponent of the surrealist generation.  A little further on, and still within the scope of public art, The Wall Man, a work by Pedro Pires consisting of five anthropomorphic sculptures oriented in different directions, with small differences between them. Composed of small iron squares that act as pixels in a photograph, these figures aim to question the concept of identity in the contemporary industrial world. Following by Passeio dos Heróis do Mar, passing by the Olivais, where there stands a River Mountain, a sculpture of Rui Sanches composed of three circular platforms cut by a wall which intends to illustrate an island of rest. The wall is torn by a window that allows to see the river, like a painting, and a mountain, represented by the block of stone.

A little further on, and still within the scope of public art, The Wall Man, a work by Pedro Pires consisting of five anthropomorphic sculptures oriented in different directions, with small differences between them. Composed of small iron squares that act as pixels in a photograph, these figures aim to question the concept of identity in the contemporary industrial world. Following by Passeio dos Heróis do Mar, passing by the Olivais, where there stands a River Mountain, a sculpture of Rui Sanches composed of three circular platforms cut by a wall which intends to illustrate an island of rest. The wall is torn by a window that allows to see the river, like a painting, and a mountain, represented by the block of stone.

Crossing the garden towards the river, enter the Passeio do Tejo, going through it until you reach the Queen D. Catarina de Bragança. This ten meter high replica of a statue built in the United States of America of Audrey Flack, by the Association Friends of Queen Catherine, to celebrate the fact that the Borough of Queens, in New York, owes its name to this queen.

Crossing the garden towards the river, enter the Passeio do Tejo, going through it until you reach the Queen D. Catarina de Bragança. This ten meter high replica of a statue built in the United States of America of Audrey Flack, by the Association Friends of Queen Catherine, to celebrate the fact that the Borough of Queens, in New York, owes its name to this queen.

In the play by Federico García Lorca, the last one written by the Andalusian author before being executed by the Phalangist forces during the Spanish Civil War, the widow Bernarda Alba takes charge, with an iron fist, of the lives of her five daughters (Angustias, Madalena, Amélia, Martírio and Adela). The house is the jail where the matriarch encloses and oppresses the drives of her descendants.

Starting from the plot of this absolute masterpiece, João Garcia Miguel (who some years ago brought to the theaters another of the essential pieces of the author, Yerma) wrote a text as if looking for “the hidden and inaccessible secret it contains.” Suppressing some characters, the show explores “a deep connection with the earth and body” that the director reveals in the writing and in the universe of Lorca. A universe he takes to himself. Therefore, The House of Bernarda Alba according to Garcia Miguel, moves away from “the gaze on daily life to dive into the depths of each one of us.”

Bernarda Alba’s character – here interpreted surprisingly by the well-known Irish actor Sean O’Callaghan – is paradigmatic of this view, as if cruelty was, in short, an expression of the human being. “To save her family, Bernarda becomes the despot. Mourning is not the catharsis, but the barbarity,” the director highlights. “At the end, this character embodies the invisible cycle between extremes that each of us has within us and that at any moment, without us understanding, reveals itself.”

In one of the points of these extremes, Bernardas Albas appears and they “grow in the cruel light of our day, becoming more and more coercive, with discourses where they admit mechanisms of repression and censorship, in the name of freedom.” But at least on this stage, rather than addressing economics, politics or society in general, “what really matters is to dig deep into the human intimate” especially in a search for everything that is beyond reason.

An international cast

In this production of Companhia João Garcia Miguel, the director has only one Portuguese actor, the young Duarte Melo, with whom he previously worked in Tio João. “He is a great performer, with an impressive physicality, one of those who has the right attributes for the kind of work e do. “ He plays the role of the housekeeper Poncia. But, as we have seen, this is not the only “suppression” of gender that the show contains, since Sean O’Callaghan plays the castrating mother Bernarda Alba.

For the actor with a vast curriculum in Shakespeare’s Globe and Royal Shakespeare Company productions, “it’s a huge challenge because this is one of the most important characters in drama worldwide. Curiously, today there are great actresses playing male characters. In Britain, it has been recurrent to see women playing Lear or Richard III. Bernarda was offered to me, and I feel that it is a work of enormous freedom, so great that it goes beyond gender.”

For Garcia Miguel, both choices allow “to avoid a predetermined image of the characters,” since “the theater is no longer the world of naturalism, but of possibilities.” And how would the director not take advantage of the possibility of having an actor like Sean O’Callaghan under his direction, he who is a great admirer of Garcia Miguel’s work?

The feminine presence is in the Brazilian interpreters, Annette Naiman and Paula Liberati, to whom Garcia Miguel gave the roles of the daughters Martírio and Adela. For both, “it’s not just about working with someone as recognized as Garcia Miguel. To do this piece, considering we left Brazil two and a half months ago, has a very special meaning for us. There are a lot of Bernardas Albas walking around there.”

After the preview at Teatro Ibérico, from the18th to the 20th of October, this visceral and exciting look on The House of Bernarda Alba will return to the same stage between December 12 and 22. Before this more extensive season in Lisbon, the show passes through Brazil during the month of November.

In the central zone of Lisbon, on the platform of the Roma / Areeiro station, the suburban train is arriving coming from Alcântara-Mar to Castanheira do Ribatejo.. Without undue delays, we enter the train, knowing that in just under a quarter of an hour we will be sitting in the comfortable lobby of Biblioteca de Marvila talking to some of the local Visionaries.

Gently sliding down the rails, the train seems to carry us out of the city through vacant lots, entanglements of freeways and overpasses that cross the track and narrow nests that lead to small vegetable gardens. As expected, in six minutes, we disembarked at the station of Marvila. A few meters to the north, without particular ostentation, but very visible, is our first destination: the Biblioteca de Marvila.

Living the programmer’s insomnia

Due to personal availabilities, only four of the 12 Visionaries of Marvila answered our call. And it is with enthusiasm that they share the experience, in this edition of Os Dias de Marvila (The Days of Marvila), of being in the role of programmers of two of the shows to be exhibited at the festival – 1.5º Ponto de Equilíbrio, from Companhia Erva Daninha, and the quartet concert DG4.

To be a visionary is precisely to play the role of programmer. The project Visionários, promoted in several municipalities by ArteemRede, allows the viewing of different shows and artistic creations to a group of people who evaluate them and will select them for future public exhibition. However, it is not enough to like – you have to check the availability of the artists, the available budget and many other aspects that, as a rule, give many sleepless nights to a professional programmer. Cila, Dina, Rui and Eunice, visionaries from Marvila, speak up! After having seen a roll of projects in loco and in video, the group, “very heterogeneous in terms of ages and life paths,” decided and it is now up to the public to evaluate their choices.

“All the punches I took were because of rap“

The reunion of old friends that the love for music, namely rap, brought together. Seated in front of us, after a photo session under a blazing sun, Viruz, Myslo and Rato Chinês joined us and quickly began to share stories that seem to come out of the songs they sing. Of the three, Rato Chinês is the only Marvilense (Viruz and his producer and DJ, Myslo, come from Campolide) and his artist name is very symptomatic of what is, but also was, the neighborhood where the library is installed nowadays. “Rato is my nickname since I was a kid. That is how, here in Chelas [name already removed from the toponímia of Lisbon, but still widely used by locals], everyone knows me. The Chinês (Chinese) is from the time when this place was almost just tents and the road was a dirt track: the Chinatown.”

Viruz and Rato met in the 90’s, in Bairro Alto, and together they were doing freestyle rap in the street, echoing the admiration they had “for the poems and the beat which they heard from the older students in the hallways of their school.” They speak of a golden period, between 2001 and 2004, in which the duo was very successful in the lively neighborhood of the capital. However, life took them down to different paths: Viruz has a well-established career in national rap and Rato is back in the art that made him take all the punches he remembers. And, in a way, it is a return that the Library sponsored: “I came in here a few months after opening, and asked for a studio. There were none, but the doors of an auditorium were opened to me.” In fact, this experience leads the trio to underline the importance of ending mutual mistrust and prejudice between the residents of the area and those who come from the outside: “and as artists, it is up to us to be mediators of these realities,” they emphasized.

Cultivate self-esteem in those who need it so much

We now cross the train track towards the Marvila Road, turning our backs to Chelas. In Azinhaga das Veigas, an old palace houses Casa de São Vicente, an association currently dedicated to the rehabilitation of people with disabilities, founded in 1940 by the Countess of Mafra, Maria Antónia de Mello Breyner. Here, Suzana Rodrigues works with some people of this IPSS in the exhibition A nossa cara não é estranha (Our face is not strange), which will be featured in Biblioteca de Marvila during the festival.

The exhibition consists of recording, through photography, images that are particularly familiar to all audiences, using the young as models and the not so young people of this House. Suzana gives us an example, showing the famous painting by Johannes Vermeer on the computer The Girl With a Pearl Earring. Then she shows a picture of the model, a female student and member of the institution, reproducing the beautiful painting, and asks us: “Isn’t she beautiful? Can you see that she’s a woman with a cognitive impairment?”

The purpose of this exhibition will be precisely to show everyone how “these people are special, that this is their other face” and at the same time to make the confidence level of these “very special people” grow. When they see themselves on these photographs, their “self-esteem can only rise.” On the other hand, a public moment of this magnitude will provide an additional motivation for many of the families to come back to meet their own. Many of the students in the House live at the institution (there are 25 females in the Home) and they have little or no contact with their families.

At the farewell, the technical director of Casa de São Vicente, Cristina Gomes, leaves us a wish: “We want to be more and more included in the city, but the city has to include us. We have lots of ideas to share.” This exhibition is surely one of them.

“A site divided into zones with letters of the alphabet”

We now head east to the apogee zone of Marvila Velha, where everything seems to be changing at an amazing pace. With the river in full view, we enter the “One Your First Stop complex”, a former railway warehouse, now occupied by creative industries and co working. Here we find the director and performer Tiago Vieira, born and raised in Marvila, and Patrícia Carreira, director and member of the Companhia Cepa Torta, accompanied by young people from her community theater project. This project involves students from the parish schools and the neighborhood community of Marvila Velha, Lóios and PRODAC. Both will present two creations in Os Dias de Marvila.

Already famous in the Portuguese theater, Tiago is the co-founder of Latoaria, in Mouraria. “I would not stage and create the way I do if I had not been born and raised in Chelas,” he explains, before going into the concept of A Pátria é a minha Revolução (The Homeland is my Revolution), a show he is organizing with a cast of actors and professional dancers, and that will be presented in one of the warehouses of the complex where we are at. For what he calls the “apocalyptic concert,” Tiago will seek out authors who marked him, such as Ortega Y Gasset, Nietzsche, Genet, Rimbaud, but also Sam The Kid, the rapper who, just like him, was born and raised in the neighborhood and sang Chelas, “place divided into zones with letters of the alphabet.” “It is a tribute to the people who marked me in Chelas, a poetic interpretation of the memories I keep, of that almost Chekhovian boredom of hot days that brought scents from the distant lands of Africa. Because in Chelas, especially in Zona J, we can still breathe deep African environments. And I do not conceive my neighborhood memories without them.”

Lara, one of the young women who participate in the Cepa Torta project, the O Mapa do Mundo Reinventado (The Reinvented World Map), intervenes: “But it’s not only Africans! My family came here from the north. They lived in a tent, there was a vegetable garden. Then there was the rehousing. And those who don’t live here continue to look at us with suspicion. Of course there is poverty, but I think that people see Chelas as worse than it really is when we talk about bad things.”

How about today? What has changed? None of the young people who are present is quite sure, but Tiago concludes: “To have a library in Chelas is something incredible…”

The last slow in Marvila

Our next destination is the Party Hall of Vale Fundão, there we meet Rui Catalão, who is rehearsing O Último Slow (The Last Slow), a show that will have two presentations in Os Dias de Marvila (although one of them will be in the Torreão Poente do Terreiro do Paço). This is a return to this territory after about two years ago, at the invitation of the Teatro Municipal Maria Matos, he created Assembleia (Assembly), a spectacle carried out by Marvilenses from two different neighborhoods: Alfinates and Armador.

“For this project, I started auditioning at Biblioteca de Marvila, where 70 people were present. Unfortunately, none, except David, who is with us, has become engaged.”

It will be David, a neighborhood youth with some cognitive limitations, who will act as a touchstone in this new creation. “It is a dance theater show, made of dramatic movement without words,” from slows, “this fashion in loss,” these songs that are part of each one of us when we are growing.

In the scene, Rui joins professional and amateur performers (some who come from creative projects he did in Vale da Amoreira), and regrets that in Marvila “it is still difficult to call in the community.” In fact, the director points out how much there is to do on the ground for people to mobilize. This is an aspect pointed out by many of the people with whom we talked. From local residents to other agents, all realize that only the persistence of social and cultural projects can definitively end the “hidden city” that one day was called Chelas.

The radiant future is the children

It could be some sort of epilogue to this trip, but we believe it to be the beginning of everything.

With the day ending, we return to the Library to discover another project that has, in that space, a house. This is the Children’s Choir of the Biblioteca de Marvila, and now that the school days are over, some young stars can pose for the photograph.

Conducted by the conductor Catarina Braga, the Choir, also sponsored at its genesis by the Teatro Municipal Maria Matos, is preparing for another year of work, still without certainty as to the number of children who will integrate it. “Last year we had 11, 12 children coming regularly to rehearsals,” says Catarina. And curiously, they come from all over the parish, so they constitute a very heterogeneous group in terms of social stratum. Although very challenging, it is a small achievement, and as a mother comments, it is “a project that is exposing the neighborhood very positively, demonstrating that things are happening here.”

One concrete example of inclusion was the participation of some Roma children. “Not being regulars, we managed to convince them to come, and we hope they do not give up. It would be very important for them,” emphasizes the teacher.

Now is the time to raise voices and start preparing the presentation planned for Os Dias de Marvila. And we had a small sample of: Cancioneiro da Bicharada by Carlos Gomes, the children present interpreted O Grilo, from a poem by Alexandre O’Neill, with choreography too.

In the future, Catarina wants to put the choir singing Marvila and, for that, has already begun a search for the repertoire of the parish, rich mainly in songs from the “marchas.”

The sun is setting and it is time to leave this side of the city. Towards the threshold, the eternally hopeful voices of the children are still heard. After all, it is with them that one begins to construct the future of the city. And the words we heard from rapper Rato Chinês a few hours ago come to mind – “In my time, we believed that there were only two ways out of the neighborhood: football or fight!”

Maybe, now or in the near future, other ways will open up.

paginations here