It’s the big surprise of this August: Lisbon will actually be hosting the FIMFA,. The International Puppetry and Animated Forms Festival, which usually happens in May. However, due to the constraints resulting from the pandemic, the event was canceled. But Luís Vieira and Rute Ribeiro, artistic directors of the theater company A Tarumba and FIMFA Lx, decided that they would not give up and, weaving their network of collaboration with various artists of puppetry and objects, as well as with some venues in the capital, set up a “lightning fast program” with eight great shows of great international names such as Agnès Limbos and Oligor y Microscopía, and Portuguese names like André Murraças, Companhia Pia, Teatro de Ferro, Formiga Atómica and, of course, A Tarumba.

“Even knowing that we are sailing by sight and living with a suspended future, we want this to be the August of our de-confinement, ” explains Luís Vieira, stressing that the Descon’FIMFA intends to give a sign of confidence to the public and show that “it is possible to return to the theaters safely, complying with all the required sanitary rules.” To “restore the harmonious coexistence, an essential condition for the theater, between artists and the public”, the festival presents shows “with very small audiences and several adaptations on the scene that, although they do not compromise the creative concept, ensure the need to restore the confidence of the spectators in theaters and on stage. ”

The theater of objects to think about our time

In the festival program, Shaday Larios, from Oligor y Microscopía, is quoted: “our objects can speak for us, when we are no longer here. Either when we refuse to speak, or due to many other absences. So why couldn’t we speak for them? ” This idea serves as a kind of hat for the alignment of the Descon’FIMFA which, as Luís Vieira points out, “finds in the manipulation of objects the formal unity”, which makes this edition of the festival something absolutely “unprecedented” in the very concept of FIMFA. Through these shows, they are “the objects that gain prominence and connect us to the emotion and humanity that surrounds them.”

The first two shows of the festival are very representative of the formal and conceptual capacity of the theater of objects to create imagery or describe memories. They are both created by Jomi Oligor (Hermanos Oligor, Spain) and Shaday Larios (Microscopía Teatro, Mexico), two artists who have worked together since they realized they were walking parallel paths.

The first, opening show of this Descon’FIMFA, is an absolute debut in Portugal and is titled La Melancolia del Turista, a corrosive approach to mass tourism that no longer exists and “to the mental constructions of paradise that the tourist seeks, but can never find”. The second, The Machine of Soledad, is an incredible story told from love letters written in the early twentieth century, found inside a suitcase in Mexico, which now returns to FIMFA, five years after passing through the festival and receiving enthusiastic acclaim from the public.

The festival closes in early September with the return to Lisbon of an artist who is considered to be “the pope of the theater of objects”, Agnès Limbos, and the Belgian company Gare Centrale. Ressacs it is an exercise in humorous criticism of the consumer society and the excesses of capitalism as it follows the odyssey of a bankrupt couple “on the brink of a nervous breakdown” after, being affected by the crisis of the sub prime, drift offshore on a small boat. As Luís Vieira points out, it is yet another show “full of irony and ingenuity by a great master of European theater.”

The Portuguese presence

Long-time partner of FIMFA, André Murraças is one of the most interesting amongst the current creators of Portuguese theater and his creations are no strangers to using the technique of object manipulation. In this Descon’FIMFA, an absolute debut: The Pink Triangle. The play marks the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, invoking the dark experience in the Nazi concentration camps of homosexual Jews.

Also a longtime accomplice of the Lisbon festival, from Gaia comes the most recent creation of Igor Gandra and his Iron Theater. A Faraway Thing it is the first phase of a film-performance, made in collaboration with the composer Carlos Guedes, where “it seeks to understand a series of peculiar events carried out by a group of emancipated objects.”

The festival’s program also includes returns to the stage of the magnificent The walk of elephants, by Miguel Fragata and Inês Barahona (Formiga Atómica), and by the bewildering “blonds” of Luís Vieira and Rute Ribeiro (A Tarumba) with This is not Gogol’s nose, but it could be… with a touch of Jacques Prévert..

Finally, a special highlight for the street theater of the PIA company, a project based in Pinhal Novo, on the south shore of the Tagus, which opens (finally!) in Lisbon, after, over its 18 years, having traveled with its giants to countless European, Asian and South American countries. In Between Worlds, large puppets take us through, with sensitivity and imagination, an area somewhere between life and death. An unmissable spectacle for the whole family that can be experienced at Castelo de São Jorge.

THE Descon’FIMFA Lx It takes place between August 5th and September 5th, with most shows to be shown at Teatro do Bairro, with the public able to take advantage of the purchase of vouchers for several sessions at a reduced price. Everything for descon’FIMFAwith proper safety measures and, of course, with theater of excellence.

At the first edition of Fair Saturday Lisboa, about 40 locations across the city hosted more than 75 cultural events for all audiences. This massive participation benefited about 45 social projects, selected by the participating organizations.

In 2020 the festival’s organizers want to once again offer a “day with a positive social impact, emphasizing the importance of developing a more just and humane society”. To this end, registrations for the second edition of this charity festival – to be held simultaneously in various cities around the world on November 28 – are already open.

Artists, organizations, institutions and socio-cultural projects can apply on the event’s official website by choosing the cause they want to support. For more information and inquiries, Fair Saturday Lisboa 2020 suggests emailing the address lisboa@fairsaturday.org.

Galeria de Arte Urbana (Urban Art Gallery – GAU), through this project, #DiariosdeArteUrbanachallenged artists to share their creative processes and art pieces they have developed since March, during the period of social isolation.

In this way, their work continues to be seen by everyone, but instead of being seen and appreciated on walls and places of artistic intervention in Lisbon, they can be seen on GAU’s web site and on its official Facebook and Instagrampages. To prove that artistic expression has no limits, the Agenda Cultural de Lisboa has spoken to five artists who tell us, in their own words, how it felt to work at home for someone who normally works on the street and on a different scale.

Vitó Julião

www.vitojuliao.com

Working from home during this period was not that strange for me, as I dedicate some time to develop projects in my studio. However, it allowed me to dedicate more time to personal projects, to reinvent myself and to give a bit of my work to the community. During this period, I made a free coloring book available to keep adults and children busy, and created a Paper Toy, also free, at the request of the Instituto Português do Desporto e Juventude. In addition, I also made several Art Prints, which I have made available in my online store , to counteract the reduction of commissioned works.

Telmo Alcobia

www.telmoalcobia.com

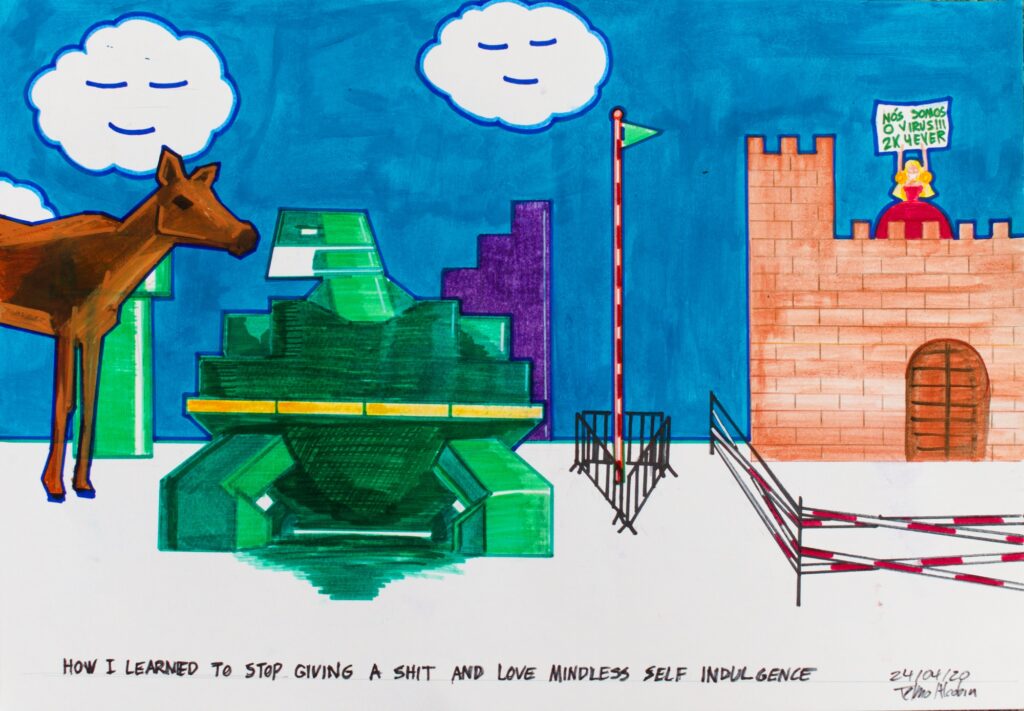

I am part of a group, POGO, which had to cancel group work, as well as the exhibition I was planning. So, since art, in my understanding, is about real life, during my isolation I watched how people reacted to these facts and emotions, interpretations, extrapolations, and conspiracies. I reduced expenses to a minimum and concentrated on what I could control. I drew in a way that was possible, in my tiny house, I drew to materialize these ideas, like a transformative diary of all this, creating a series of works entitled Desenhos de Quarentena (Quarantine Drawings), based on albums and songs that kept me company during this season.

Tamara Alves

www.tamaraalves.com

Ozearv

www.instagram.com/ozearv

UtOPiA

www.utopia-arts.com

In the quarantine nothing changed my professional routine, since I do a lot of work in the studio for several collectors at mundo.Na. In fact, I had far more orders during this period. I realized that people, as they could not leave their homes, felt the need to obtain art works as an investment and for pleasure. In fact, I had a lot of requests that I could not fulfill. In other words, I ended up painting twice more than usual, sending out more than 50 canvases to different countries in Europe and the rest of the world. In addition, all shipments were safe and fast.

The collaboration resulted from the pandemic crisis and consists of sharing events online between the Argentine and Portuguese capitals. The initiative was launched the Buenos Aires City Council, whose official sitewill create an international content sharing network for the Culture at Homesection.

Starting in June, the Lisboa Agenda Cultural website will host this collaboration between the two city councils by sharing the content made available online by the city of Buenos Aires.

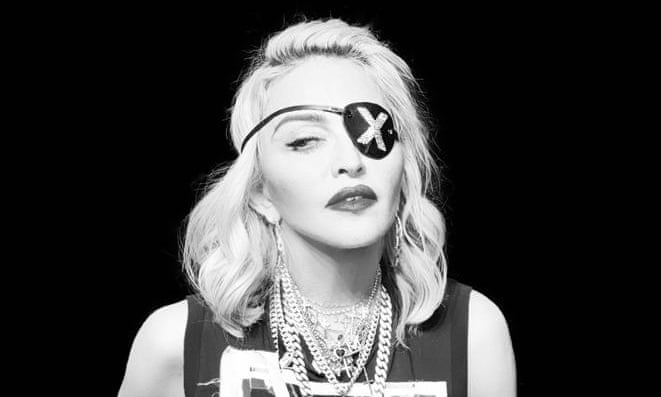

In January, the Coliseu will host eight shows of Madonna and Campo Pequeno will be the stage for the concerts of James Arthur and Keane. Next month, Devendra Banhart will perform twice at Capitólio and Aula Magna will welcome the Tindersticks..

In March, the Americans Cock Robin will perform at the Coliseu for a nostalgic audience. April will bring Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds, and Bon Iver to the Altice Arena. And May will be a month of great shows: the British Michael Kiwanuka will perform at Campo Pequeno, the German band Alphaville will be at the Coliseu, and Harry Styles will be at Altice Arena.

In June, it will be the time to see James Blunt again at Campo Pequeno. And in July, choosing promises to be difficult: Altice Arena welcomes Kiss, Aerosmith, and Lenny Kravitz. In November, the phenomenon André Rieu will return to Altice Arena.

Outside Lisbon, more specifically, at Passeio Marítimo de Algés, and before the arrival of NOS Alive which stars Kendrick Lamar,,Taylor Swift,, Billie Eilish, and Faith No More, May 20 is the starting date of the second phase of the European tour of the Not In This Lifetime Tour of Guns N’ Roses..

On the day that marks the 5th anniversary of Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen’s death, one of the most beautiful panoramic viewpoints in Lisbon was named after her. A monument was erected at the location, a bust sculpture of Sophia, a replica of the original in bronze, carved in the 50s by António Duarte (1912-1998). Sophia very rarely talked about Lisbon in her poetry. Having an appreciation to great natural spaces – the sea, the mountains and the plains – she sometimes expressed her dislike for the life “enclosed” between the “walls of the houses and buildings” of the city. As in the rightly titled poem: “City”:

(…)

“Knowing that you take my life in you ,

And that you drag through the shadows of the walls,

My soul that was promised,

To the white waves and the green forests.“

On the monument, a plaque evokes one of those rare poems, titled “Lisbon”, which opens her book “Navigations”. In 1977, Sophia was invited to take part in the celebration of Camões Day in Macau. While flying over the East for the first time, she thought of the men who had arrived there 500 years before, not knowing what we know today.

“Theynavigated without the map theymade.”

The trip to Macao triggered a reflection on what it would have been like for Portuguese sailors to reach the brave new world: all the colors being revealed, the smells, sounds – all the amazement and the vertigo of finding that distant and fascinating reality.

Lisbon thus emerges as the symbolic starting point of the Age of Exploration, the familiar place that was left behind for the uncertainty of the new world. Lisbon was a great path to the sea.

(…)

“As the wide sea to the west expands

Lisbon oscillates like a big boat“

In the center of the garden, a bronze figurative statue by an unknown author, entitled “Mother and Son”, evokes the maternal relationship. Possibly influenced by “Flora” by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, a depiction of the goddess of flowers and spring. This statue with its winged figures suggests a Hellenistic representation related to Greek culture and ancient Greek mythology. It is therefore the ideal place to remember Sophia’s passionate relationship with Greece.

The first contact with the Greek civilization came when a very young Sophia discovered Homer. She was immediately dazzled by Greek things, by the Odyssey in particular, and immediately developed a strong attraction for the Greek deities. In her first books, “Day of the Sea” (1947) and “CoraI” (1950), she shows her fascination with Dionysus and Apollo, Greek gods representing the impulses of nature.

Sophia already loved Greece, and held a fascination for its sea, its islands, its light and colors. And in the 60s, she made contact with them physically. She first visited Greece in 1963 with Agustina Bessa Luís. Since then, whenever she could, she would return. She returned with friends, with her husband, with her children, and with her grandchildren, perhaps in search of “a divine and multiple conscience,” evoked in one of her “first Greek poems”: “Evohé Bakkhos.”.

On November 27, 1946, Sophia married Francisco Sousa Tavares, in Porto. In 1951, Sophia, her husband, and their three children, moved to Lisbon and started living at number 57, 1st floor, in Travessa das Mónicas. Francisco ran for sub-inspector of labor at the Ministry of Corporations.

Once she was at home, she wrote a postcard to her mother:

“I am in a state of grace! I arrived today. I spent this week opening and unwrapping the things you sent me. They are so beautiful. They match the place so well. I have everything that I need! The house is beautiful! (…)”

In the poem “The Houses”,she writes:

“There is always a fantastic god in the houses

Where I live, and around my steps

I feel the great angels whose wings

contain all the wind of spaces.“

At Sophia’s house, there were always guests. Everything was a topic of discussion. Freedom was lived before it existed. Salazar starts to hear about Francisco Sousa Tavares, when his activism in the monarchical movement became more active.

In 1958, both gave their support to Humberto Delgado’s campaign, which results in the dismissal of Francisco Sousa Tavares from the civil service.

It is in the 1960s that the political struggle and indignation against the dictatorial regime is revealed in Sophia’s poetry. In the “Sixth Book” the most direct poems of criticism and opposition to the regime are present, one of them is: “Old vulture”, obviously addressed to Salazar:

“The old vulture is wise and smooths its feathers,

Rot pleases him and his speeches

have the gift of making souls smaller. “

This book led the Portuguese Writers Society to award Sophia the Poetry Grand Prix.

In the early 70’s, she would dedicate beautiful poems to Che Guevara and Catarina Eufémia (comparing the peasant girl from Alentejo to Antigone due to their search for justice). In the extraordinary poem titled “Camões and Tença”, she establishes a painful parallel between 16th century Portugal, which did not recognize its greatest poet, and the contemporary country:

(…)

“This country kills you slowly ;

The country you called and you don’t answer;

The country you name and are not born .”

(…)

Next to the Panteão dos Bragança, we evoke Sophia’s aristocratic descent and relationship with her surroundings.

On the maternal side, her great-grandfather was Henry Burnay, of Belgian descent, and the 1st Earl of Burnay, a title granted by King Louis I. Her grandfather was Tomaz de Mello Breyner, the 4th Earl of Mafra, was appointed Royal Chamber Physician by King Carlos I. It is to him, who taught her how to memorize poems by Camões and Antero, that Sophia owes her true initiation into poetry.

Sophia was born in Porto, Rua António Cardoso. Very close, in Campo Alegre, her paternal grandparents’ house was a farm with a huge romantic garden with several greenhouses of exotic plants, numerous fruit trees and lakes. A “fabulous territory” where enchanted worlds easily emerged, is the origin of the stories that Sophia would write for children.

In 1962, when she published “Exemplary Tales”, some of these narratives were understood as fierce criticisms of the world to which Sophia belonged by birth and class. The tale “Monica’s Portrait” satirizes the National Women’s Movements, which constituted the support structure of Salazar’s regime. Shocked, some friends of Sophia even questioned her about this text: “How could you, even more since it is a world you know from the inside?” Sophia replied, “This world you speak of, which I know from the inside, has no inside, only outside.”

“When I die I will return to search for

the moments I didn’t live by the sea“

The wonderful view over the Tagus pouring out into the ocean is the starting point for the evocation of the sea as a convergence with Sophia’s poetry.

The first sea that emerged in Sophia’s life was the Atlantic. The sea of Granja beach, where Sophia spent an enchanting summer in a rather small house situated on the dunes right above the sea. She would go straight to the beach, and spend hours bathing in the natural pools that, at low tide, surfaced on the south side of the beach. Sophia wrote numerous poems in Granja:

“White house on the huge seafront,

With your garden of sand and sea flowers,

And your intact silence in which you sleep,

The miracle of things that were mine.“

As she wrote in Greece after discovering the intense blue of the sea and in the Algarve, on Dona Ana beach where the similarities with Greece were evident.

“This is the dawn I expected

All day a clean start,

Where we emerge from night and silence,

And free we inhabit the substance of time.”

In this poem, Sophia talks about the Carnation Revolution of April 25th, 1974, “The whole and clean initial day.” A few days later, on May 1st, thousands of protesters took to the streets. In a meeting at the Writers’ Association to prepare the demonstration and phrases for the parade, Sophia suggested “Poetry is on the street.” Maria Helena Vieira da Silva immortalized that phrase in a poster she painted.

Sophia was a deputy for the Socialist Party in the Constituent Assembly and bequeathed us her most beautiful definition of socialism: “Socialism must be an Aristocracy for All,” a way for everyone to reach the same realms that only the aristocrats and the privileged accessed since it was the environment in which they were born.

Sophia died in Lisbon on July 2, 2004. She was moved to Panteão Nacional on the 10th anniversary of her death. She wrote in the poem “I Will Return”:

“I will return to the poem as the homeland to the house ,

Like the old childhood I lost out of carelessness

To obstinately seek the substance of everything

And scream with passion under a thousand lights.“

Is it true that you were discovered by chance while singing with some friends at a table next to Rodrigo Leão and Gabriel Gomes?

Back then I was 17 years old and Bairro Alto was a very mysterious place, very different from what it is today, with some small bars and clubs. My friends and I would go to all these places, and these night outings had a special charm because I was always singing – I had a friend who would always ask me to sing when we went out. This boosted my love for singing, as it gave me some feedback, the enthusiasm of the people who clapped and asked for more. On that particular day we were at Gingão, and Sétima Legião came in. They were looking for a singer, and I think I was the 14th singer they listened to. There is a very funny story related to that episode: Pedro Ayres was in Brazil and Rodrigo took the audition tape to the airport so he could hear it. Then they called me to work with them, and I never stopped since then.

You were only 17 when you joined Madredeus, which was an innovative project in the Portuguese music scene of the 1980s. Did you realize right away that the Madredeus sound was something unique and innovative?

The group was received, from the very first album, with a lot of enthusiasm by both the public and the critics. We recorded the first album in 1987, and at the end of the following year we were invited to the Bologna Young Artists Biennial. That’s when we realized that even people who did not understand the language actually loved our music. When this adventure began, I had no idea that music was going to be my life – although I wanted that. Music has always been a great company. As an only child, I spent most of my time listening to music and singing. I was fortunate to join a group that introduced me to a repertoire that was both familiar and completely new to me, and which ended up having a great impact on the public. The first few years were marked by a lot of enthusiasm, not least because we were entering a very different era from the one the country had experienced in the previous decade. Madredeus had a very Portuguese flavor, coming from tradition but renewing it. We had a different language, an intimate atmosphere, a quietness… I think we didn’t realize that right away, not like we do today when we look back and see what we did. I was singing songs that touched my heart, with which I could relate, and that sentimental aspect had a great impact on the public. My life slowly became the opposite of what I had experienced until then, as an only child who was studying and had never gone abroad. The first album was recorded in three nights at Teatro Ibérico. We had to play at night so as not to record the sound of the tram [laughs].

Did your parents encourage you?

I studied piano and when I started singing I was at Academia de Amadores de Música, but I wasn’t too serious about it. At home I would often create Song Festivals with my cousins, who lived downstairs. Singing was a constant presence and a company. When I started going out at night and singing during these outings, I was in love with two records my parents had at home, and which had a huge influence on me. One by Amália (the one with the bust on the cover and the song Abandono ), and Zeca Afonso’s Cantigas do Maio. Those were the songs I would sing when I went out at night.

You left the band in 2007. Did you feel it was time to pursue a solo career?

Our lives had changed, we had built our own families, so we had to manage our calendar differently. The first calendar lasted ten years; the second, another ten. But in the meantime, we stopped for a year to think about how to organize this. We had talked about having three or four months of very intense activity and then each one would do other things, not least because some band members had other projects. That year I recorded two albums produced by Pedro Ayres de Magalhães, and another album at the invitation of Polish composer Zbigniew Preisner – Silence Night & Dreams, recorded by EMI Classics. It was a very intense year in which I toured with these three projects. At the end of the year, when we discussed our calendar again, I got a very different proposal: a seven-year priority contract (not exclusive). It was either that or leaving the band. I was surprised by the inflexibility, but since things were like that, I decided to leave. For the first time, I said ‘no’.

But you never gave up on music…

In the meantime, I joined a repertory creation group and I started creating some melodies and writing some lyrics. With Madredeus I sang what they gave me. I had some room for creativity, but it’s not the same as having total freedom to create your own lyrics and melodies. This group did not go on, but I liked the idea of having a group of musicians with whom I would create a repertoire – which happened later, in 2011. I did a lot of things before that: I was in Italy, where I sang with the Solis String Quartet, while also creating concerts and writing arrangements, always looking for the right musicians to create that environment of great dedication. It finally happened in 2011, and in 2012 I recorded my first album, Mistério, and then the second one, Horizonte, in 2016. Between these two albums, I did another record in which I wrote the arrangements for several Mexican and Latin American songs.

You have worked with several internationally renowned artists such as José Carreras, Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil. Is there anyone you would like to work with?

I never thought about it. These collaborations have always been fleeting meetings, invitations I received. Only recently, in May, at a show I gave at Casino Estoril, did I invite two people to join me: Marisa Liz and Sara Tavares. Two women I admire deeply, with very different but equally charming personalities. Very strong and dedicated women I met Marisa when Amor Electro invited me to sing with them at Campo Pequeno, and I’d been following Sara’s career for many years, always with great interest. I’ve always liked her music. I invited the two of them, and I think it was wonderful.

Did you find it difficult to transition from being a singer to being a songwriter?

I was very happy when I found out I could do it. When we recorded the first album, we wanted to go to a place where we could focus entirely on our music, without any distractions. We stayed at Arrábida Convent (owned by Fundação Oriente, which generously lent us the space for a month). I had a lot of songs without any lyrics yet, but things flowed and went very well. Things were just waiting to come out. Somehow, I knew what I wanted to say. So the words came out and slowly fit into the metrics. The second album was more complicated, because it was more difficult to find the time to be fully available. I thought it would work the same way but I was completely wrong – things never repeat themselves. I tried to repeat the process but it didn’t work, not least because there were some distractions.

What gives you the most pleasure: singing other people’s lyrics or your own?

They are very different things. When I sing something, I relate to the words, even if they aren’t mine. I embody the character. It’s not like that with own lyrics. Although my lyrics are not autobiographical, they reflect my ideas, my philosophy of life. I feel more comfortable with my lyrics, I feel greater freedom. They are different but equally captivating.

You will always be associated with Madredeus. Do you see that as a burden or a source of pride?

I wouldn’t say it’s a burden, but sometimes it can be a bit limiting. People think of Madredeus as a distant band. Although we played a lot of concerts and sold out concert halls all over the world, it wasn’t the kind of music you’d hear on the radio, it wasn’t massive in that sense. People tend to downplay the influence Madredeus actually had. I can’t see it as a burden because it’s part of me, it’s what I am. It’s inseparable from me, it’s my musical DNA. It was 20 years. It’s a big part of my emotional structure. As time goes by, I can see things from a different perspective. So much so that it now makes sense to give a concert where I focus more on the group’s music.

25 years ago, you played a unique show for the premiere of Wim Wenders’ Lisbon Story . What memories do you have from that experience?

It was a beautiful coincidence. The label had just decided that our next record would be released in 32 countries. Back then [1994], Lisbon, which was the European Capital of Culture, commissioned a documentary about the city from Wim Wenders, and he asked us to use our music as the soundtrack. We hadn’t recorded anything for three years and we had a lot of new songs, so we suggested using an all-new repertoire. During a studio session, instead of recording one record, we recorded two. The music became the storyboard for the film and gave rise to a script that embodied Wim Wenders’ vision of Lisbon, so he eventually invited us to star in the film. It was a very enriching experience. For the band it was extraordinary because we ended up releasing our albums all over the world, and because we were part of a movie that opened up a new audience we might not otherwise reach. People still tell me it was with the movie that they discovered us.

What next?

I have written several things, loose things. I wrote a song based on a poem by José Saramago, called Alegria [Joy]. That joy marks the beginning of a new cycle.

Despite a multifarious work covering design, painting, illustration, ceramics, embroidery and furniture/interior decor, Sarah Affonso remains, 120 years after her birth, relatively unknown to the public. Her marriage to the Promethean figure of Almada Negreiros and the fact that she was born in a country that raised serious obstacles to female artistic expression have greatly contributed to this fact.

However, Sarah was one of the first to overcome such obstacles to the affirmation of women as artists in Portugal, back in the early decades of the twentieth century. She was the first woman to frequent – against all conventions – Café Brasileira in Chiado, which reveals not only the prejudices of her time but also the independent spirit with which she faced them. Her art also drew on a language and themes of her own, using her experiences and memories as raw material.

The painter spent two seasons in Paris which would prove crucial to her artistic evolution – the first in late 1923 and the second in 1928. She saw exhibitions by Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse, collaborated sporadically with Sonia Delaunay, and studied the work of Georges Braque and Marie Laurencin, with whom he shared a taste for female portraits.

In this context, Sarah Affonso’s work reflects a widespread resurgence of figuration in postwar European art. In her case, it was an intimate and sensitive figuration – an unprecedented approach in Portugal that explored a feminine and family universe and transposed folk art and imagery from her childhood in Minho (Northern Portugal) into a modern, cosmopolitan art.

José-Augusto França’s magnum opus 100 Quadros Portugueses no Século XX(100 Portuguese Paintings in the 20th Century) dedicates a beautiful text to Sarah Affonso’s Sereia (Mermaid, 1939):

“The best thing about this painting, which is inspired by folk religion and the painter’s memories of Minho, is that its protagonist is the naked rosy mermaid, with her golden hair, rather than Our Lady of Salvation! Catholic grace is superseded by the grace of art…”

The text goes on to perfectly outline the painter’s main contribution to coeval Portuguese art and her paradoxical and unique position in it: “Emerging in ‘independent’ showrooms in 1930, the painter brought a breath of fresh, delightful air to exhibition halls… a childlike taste for poetic innocence, in an unusual dimension of modernism which somehow retained its ability to create original objects – all the way (if it were to make history) to the final and synthetic structuring of Almada’s paintings in Lisbon’s maritime stations, six or seven years later – in a chronological logic in which Sarah Affonso, Almada’s wife and colleague, fits without fitting. Which, by the way, is her situation in the Portuguese painting context of her time.”

Sarah Affonso occasionally leaves portraits aside – her work’s most distinctive feature – and opts to include certain aspects of Minho’s folklore in her compositions: traditions and fairs, processions and pilgrimages, along with folk mythologies. These works show that the city of Viana do Castelo has left a mark in her childhood and teenage years, and that Minho’s special character has stayed in her memory.

In 1962, António Pedro highlighted “the delicious originality of this folkloreless painter’s Minho adventure – the Minho I speak of lies in the memory of taste, not in anecdotes, and is therefore a category, not an accident.”

The exhibition at the National Museum of Contemporary Art, along with its catalog, aims to fill this lacuna and publicize the work of one of the most notable Portuguese modernists – a tribute to an artist who, despite all constraints, created a language of her own and knew, in the words of museum director Emília Ferreira, how to be a “skilled weaver” of her time.

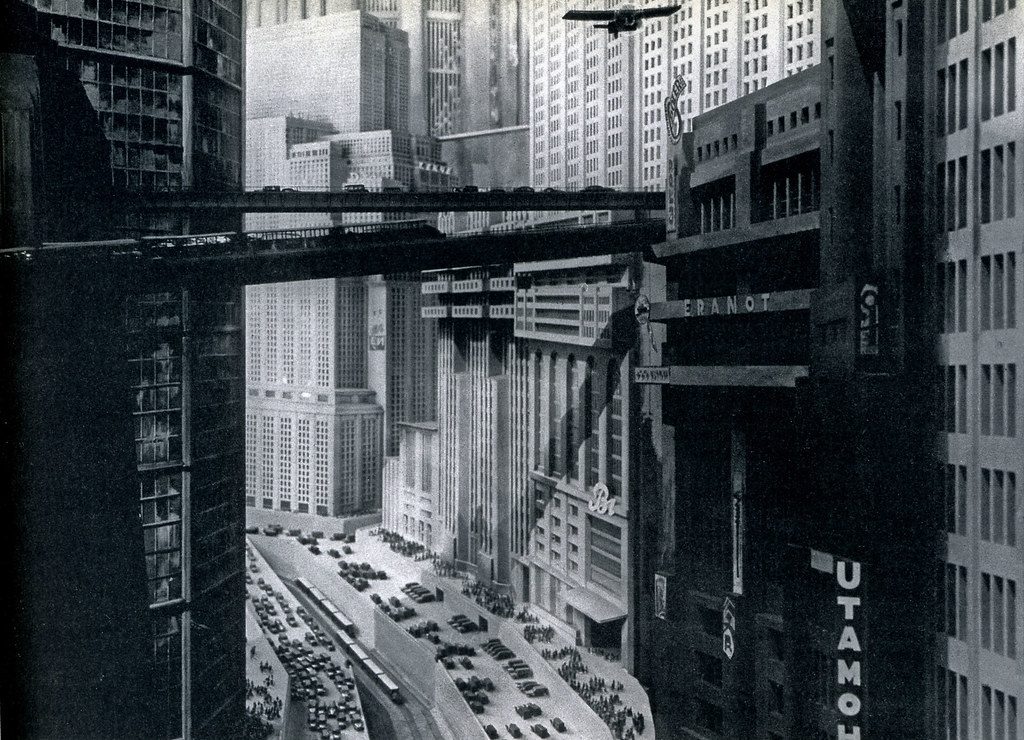

Before directing Metropolis, Fritz Lang was already one of the most reputed German filmmakers of his time , in large part due to the hugely successful ‘Dr. Mabuse‘ (1922), which would have several sequels. Not surprisingly, Lang was given green light to shoot ‘ Metropolis‘, which would become the most expensive film ever produced by UFA (Universum Film AG), a German company hoping to conquer the US market with Lang’s new opus.

As pointed out by Filipe Raposo – the composer invited by São Luiz Theater to write a new ‘ Metropolis‘ score almost a century later – “Lang would travel to New York in the mid-1920s, which would prove crucial to the film.” On that trip to the ‘New World’, haunted by Manhattan’s gigantic skyscrapers, Lang and his wife, screenwriter Thea von Harbou, came up with the idea to write a story about a city where the dominant class controls everything from its skyscrapers, while workers are taken underground to man the machines that keep the city alive.

The production process was epic in itself, involving thousands of extras and unprecedented resources. But neither UFA conquered America, nor Lang would see the movie he dreamed of in theaters. Due to strictures imposed by censors and producers, Metropolis premiered with little over 80 minutes – the version which presumably was shown at São Luiz Cine in 1928, with Pedro Blanch conducting a chamber orchestra and Gottfried Huppertz’s score.

Running at about 120 minutes, the version we will now see – with a new score commissioned to composer and pianist Filipe Raposo to celebrate both the film’s premiere in São Luiz Theater and the venue’s 125th anniversary – is the version that dazzled audiences around the world in the 1940s and 1980s. “We opted for this version, not the latest one – which runs at two and a half hours – because it is the closest to the to version one that premiered here.

” Although Raposo has accompanied Lang’s film on his piano on several occasions, ‘Filipe Raposo meets Fritz Lang ‘ is “a completely different experience.” “The challenge was to write a new score for the film’s 120 minutes and for the same number of musicians who were here in 1928.” The Portuguese Symphony Orchestra’s chamber ensemble will be conducted by Cesário Costa.

Writing the new score “took over three months,” and Raposo hopes his music will be able to “depict the future” while also endowing Lang’s Metropoliswith a current approach. The composer thus believes his soundtrack is radically different from Gottfried Huppertz’s, “because my understanding of the film, both historically and sociologically, is necessarily different.

” Raposo says his score reflects three major themes addressed in the film. First, “cities and the future,” with all that “architectural verticality” reflected in the music. Second, class struggle, “represented with much turmoil.” Finally, passion and seduction, “present in both the emotional and political realms, with my music revisiting such composers as Bach and Jean-Philippe Rameau, in which there is an idea of seduction associated with winding melodies and very balanced harmonies.”

Filipe Raposo’s encounter with the images of the future imagined by Fritz Lang thus promises to be a fascinating experience located between the music of today, the music of tomorrow, and the timelessness of great cinema in São Luiz Theater’s most noble hall.

Where does your passion for discovering new music come from?

Several people in my family are classical musicians. I don’t know if that passion is genetic or not. There were not many records in my house, but the radio was always on. My father had a habit of turning on the radio at lunchtime, and that’s how I listened to music. Perhaps because some of my relatives were musicians, my parents made me learn an instrument. After a few years I realized I was better at choosing records than at playing music. This happened in 1986, when I started working at a pirate radio station. I was one of those kids who always went to school with records or cassettes under their arms.

Your passion for radio came later?

It happened by chance, I had never thought of doing radio. I’ve always enjoyed listening to the radio, for the music rather than the hosts. Up to a certain age I would listen to Luis Filipe Barros, Antonio Sérgio or Rui Morrison’s shows… I wasn’t very selective about the music, I would listen to everything: Jimi Hendrix, The Doors, U2, or even Rod Stewart. One of the first records I bought was Frank Zappa’s Ship Arriving Too Late to Save a Drowning Witch (1982), when I was about 14 years old. Back then I was thirsty for new music, only later did I become more selective.

So you used to spend a lot of money on records…

My father would give me money to eat at school, but I would save that money because I knew that after a few days I would have enough to buy a record. For a while my mother wondered why I spent so much money on records. My father soon understood the path I was taking. Just as he tried to be up-to-date on medicine, which was his professional field, so I was trying to be up-to-date on music.

You must have a huge collection…

I do. It’s not easy with the house movings… I used to have them in a big house. Now I have them all in a small house. I’m in the process of moving again, and again it’s not easy to transport them.

Does a music lover like you buy digital formats?

I stopped buying CDs but I still buy vinyl and digital formats. Digital music – and I work with this format a lot – has a major disadvantage: you don’t establish a connection with a file, unlike the physical object, with which you create an emotional relationship. But I started using this format very early on, in part because of my thirst for urgency, because I wanted to access it as soon as possible. Music was made available at night and I could use it the next day.

Thanks to technological advances and the creation of streaming platforms such as Spotify, younger generations have a more detached relationship with music. And what do you think of that?

When I feel nostalgic, like ‘those were the days’, I realize I’m doing what my parents did, and I don’t want to be that guy. In fact, we used to consume bands and music styles. A person born in the punk orpost-punkera would consume this kind of music and eschew electronic music, metal, and so on. Younger generations today consume music in a completely different way: they tend to consume singles from many different bands. They also have a different concept of time. They like the sound of the 2010s, but they can also listen to older stuff (when listening to music on YouTube or Spotify you always get related tracks). When we were digging for records at the store there were things we would immediately reject without even giving them a chance. I think this generation is more about songs than bands. Music is consumed much faster these days. A three-month-old album is already considered an old record, unlike a few years ago, when an album would begin to come to life only after three months.

You’ve been doing your Indiegente show on Antena3 for the past 22 years. You helped launch many bands over these years…

The artists have all the credit. I may have helped a lot of bands, and maybe I’ve missed out on many others, but I’m still doing radio the way I did in the beginning: sharing the records I like, which is basically what I did back in school, except that radio allows you to reach more people. The idea is to help artists grow because they earn more fans, but also to help people expand their minds by discovering new music. I love it when someone comes to me and says, “I learned how to listen to music with you.” Last year, the first live edition of Indiegentewas attended by people from such faraway places as Bragança and the Algarve — and there was a hurricane that day, so that made me very happy.

How did you come up with the idea of hosting the show live?

In the second or third edition of the Reverence Festival, I told the organizers about the idea of having an Indiegentestage. Some of the artists I had in mind had already been invited to play there, but they had refused because they didn’t agree with the gig fees. When I invited them, they said ‘yes’. They told me, “You’re doing the dirty work, as we wouldn’t say ‘no’ to you. Maybe you should think about organizing something of yours instead of organizing it for others.” The idea stuck, and I thought about doing it to celebrate the show’s 20th anniversary, but for logistical reasons it didn’t happen. It happened last year, on the 21st anniversary. I basically needed a room and to feel I wasn’t compromising my financial future.

How was the band selection process for this new edition?

This line-up is riskier than last year’s, which had more big names. That line-up had been in my head for a long time, as it had been planned for the previous year. This year things didn’t happen that way, because I wasn’t sure there should be another edition.

Why?

I had many doubts. I thought last year was going to be a one-off event, but the feedback was very positive, not only from the audience and the artists, but also from Pedro Valente (stage manager) at Azáfama Produções. I left with the feeling that it had been an early Christmas party. It only made sense to have another Indiegente Live if it were held at Lisboa ao Vivo again, and if I could have the same people organizing it with me.

Does that mean there could be a third edition?

Let’s see where the wind blows. I won’t say no again, unless this year’s edition ruins me financially [laughs]. The question is whether it makes sense to hold another edition, whether it is relevant or not. This year I invited some people I had planned for last year’s edition, but the list was so long I couldn’t include everyone in the lineup…

The whole concept is to invite artists to interact with one another. What can we expect from this edition?

This year we have lesser known but emerging names such as Algmacena (Alex D’alva Teixeira and Ricardo Martins), Deadclub, Knot3 (Selma Uamusse and Toni Fortuna), Nancy Knox, Violet… There is some buzz around these acts but nobody really knows what will come out of there… Anarchicks will also play, and it’s curious because I first saw them in Seixal a few years ago, at an event organized by me. It makes perfect sense to meet people I came across many years ago, especially when I think they are at their height.

Expectations for October 19?

My idea was to bring together experienced artists (such as Bizarra Locomotiva or Parkinsons) and some new faces. I’m very curious to see what they will do. For instance, I’m curious to see what Rui Maia will do with Anarchicks. Last year’s bill included the names of all artists. This year there may be some surprises [laughs]. One of the bands even made an interesting suggestion: having Manu De La Roche [burlesque artist] perform at the same time.

Are there any plans to bring Indiegente Live to other cities?

It has not been ruled out… If there is a third edition, I think it will make perfect sense to do it in Porto, as many Indiegentebands come from that region and it’s not easy to bring them to Lisbon due to logistical reasons. It would be easier if I had some sponsors, of course. [laughs]

paginations here