Situated in the region where the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers flow into the Bay of Bengal, in South Asia, Bangladesh is marked by lush vegetation and many canals. Most of the country is low-lying plains, fertilized by floods from the many rivers and waterways that cross them. But rivers, during the flood season, also cause great destruction in the most rural areas.

This is, in fact, one of the biggest problems the country faces and, therefore, Marina Tabassum, in a work that responds to the social problems of communities and climate challenges, taking advantage of local resources and knowledge, designed, together with her team, a low-cost modular and portable construction system. “Many people lose their homes due to rain or lose makeshift shelters in fires”, says the Bengali architect and educator.

In Materials, Movements and Architecture in Bangladesh, Tabassum presents some of her works built since 1995. Among them, stand out responses to urgent problems, such as the living conditions of the 1.2 million Rohingya refugees or the transformations imposed by the rise of sea level, like a life-size model of one of the houses she designed, entirely made of bamboo, which makes the homes airy, safe and accessible.

Working in Dhaka, capital of Bangladesh, Tabassum, who has sought to establish an architectural practice that is both contemporary and rooted in place, develops ideas that range from how to use resources to community involvement strategies. In her internationally recognized work, the architect takes advantage of the characteristics of materials and explores light to qualify the physical dimensions of the space. Furthermore, and according to curator André Tavares, one of her main advantages is the ability to “carry out major transformations through small interventions”.

The exhibition, which is also curated by Vera Simone Bader, brings together installations, videos, photographs and everyday objects from these populations, and also aims to bring good news from Bangladesh, sharing in Europe the lively intellectual scene fueled by the flow of rivers in that country.

Materials, Movements and Architecture in Bangladesh can be visited until September 22.

Pedestrian trails and cycle paths, parks, gardens and viewpoints make Monsanto the ideal place for a day spent with family, friends or even alone. We propose a walking tour in the Park, one of many possible, which allows you to appreciate its scenic beauty and use some of its equipments.

MORNING

Mata de São Domingos de Benfica is one of the possible entrances for pedestrians or cyclists in Monsanto and a good start for a day of outdoor activity. Exploring the park with a walk along one of the walking trails is the best way to enjoy the calmest, greenest corners. The first stop is at Monsanto Interpretation Center, which serves as the reception for the Monsanto Forest Park. It has a public service area, the Documentation and Information Center, an auditorium and organizes exhibitions, workshops and visits. There you can rest before resuming the path towards Parque do Calhau which, with its large clearings, offers a maintenance circuit and a magnificent viewpoint over the east of the city. Leaving this park, and continuing south along the Water Route, you arrive at Alto da Serafina Recreational Park.

LUNCH

At Alto da Serafina Recreational Park, or Parque dos Índios (Indians Park), you can take a lunch break, using the picnic area for a picnic or, alternatively, the restaurant. Next, it is possible to explore the various recreational facilities, aimed at different age groups: playgrounds, a children’s driving school, an adventure park and the viewpoint where you can enjoy a stunning view over the city. Large lawns, trees and bushes, the presence of a small lake in Praça dos Ciprestes invite you to relax.

AFTERNOON

Continuing along the Vila Pouca – Bela Vista route, the path leads to Alvito Recreational Park, in the south. Here, there is also a varied range of recreational, sports and leisure equipments. It’s the ideal space to rest on the lawns, surrounded by woodland. The children’s playground invites the little ones to have very fun moments. There are also picnic and restaurant areas, a sports center and an amphitheater. Leaving Alvito it is possible to walk along Alameda Keil do Amaral, which allows walking and cycling and has a maintenance circuit for the elderly, a skate park, a picnic area, a dog park and a kiosk with a terrace. To end the day, there is nothing better than watching the sunset at the Keil do Amaral amphitheater, which is also a viewpoint with a unique view of the city of Lisbon.

The European Capital of Innovation award, awarded to the city at the end of 2023, legitimizes this claim. It also brings one million euros that the Unicorn Factory intends to invest in projects that put technology at the service of social innovation and the fight against exclusion. In this sector that wants to change the city, not everything is accessible, but there is room for everyone. We present four spaces where ideas are born and take shape.

HUB CRIATIVO DO BEATO

Rua da Manutenção, 71

hubcriativobeato.com

It is one of the main addresses of innovation in Lisbon and this is, precisely, the main selection criterion for companies and projects that set up shop here. Occupying the factory area of the Former Military Maintenance, Hub Criativo do Beato will, when fully rehabilitated, be one of the largest spaces of its kind in Europe, with capacity for 3000 jobs. Of the 18 buildings in the complex, five have been restored and 15 are under contract, project manager José Mota Leal tells us.

The offices of Web Summit and Unicorn Factory are located here, a structure that, in just two years, attracted 54 new technology centers to Lisbon, coming from 23 countries. Here large multinational companies such as Sixt operate, information technologies are developed (Claranet), art is combined with technology (Interactive TechnoIogies Institute) and bacteria are transformed into protein (Microharvest). For now, the presence of services is noticeable with the Square, a restaurant and market area where national products have exclusivity.

A museum, to be installed in the old Grinding Factory, is expected to open soon, and a co-living space.

CIM – CENTRO DE INOVAÇÃO DA MOURARIA

Travessa dos Lagares, 1

facebook.com/mourariacreativehub

It was the first municipal incubator to support projects and business ideas in the areas of cultural and creative industries, such as design, media, fashion, music, tiles, jewelry, among others. In addition to providing fully equipped jobs, tailored training and consultancy, or a wide network of mentors, CIM also provides support for incubation services in terms of management, marketing, legal advice, product and service development and financing.

At the moment, the center has 13 projects in development, mainly in the areas of fashion design, communication design, design for sustainability, product or textile design, which arrive there “through calls or open applications throughout the year”, says Rosário Pedrosa, CIM’s coordinator. “After the selection is made, the projects are incubated for a maximum period of four years, during which each project can have up to four jobs,” she adds.

“Our main focus is working for residents, with workshops, masterclasses, open days, speed dating, etc., but we also work for creatives in general, as well as for the community”, highlights Rosário Pedrosa.

FABLAB LISBOA

Rua Maria da Fonte, 4 – Mercado do Forno do Tijolo

fablablisboa.pt

“FabLab is a place where you can do almost anything. And its main objective is training. Always has been and always will be.” It is André Martins, coordinator of the space, who guarantees it. “We do this training through the democratization of access to tools, namely digital manufacturing and prototyping tools”, he adds. Almost anything can be done there, as the primary purpose of this laboratory-workshop is to transform ideas into reality.

Open since 2013, it operates in Mercado do Forno do Tijolo and offers accessible and safe industrial equipment, such as small and large milling machines, laser cutting and vinyl cutting machines, 3D printers, an electronics bench, computers and their respective computer programming tools supported by CAD and CAM software.

Being accessible to citizens, by appointment, FabLab promotes open days on Mondays and Tuesdays, where the use of the machines is free, always under the watchful eye of the responsible team. This space for sharing knowledge and experiences is, according to André Martins, “increasingly a laboratory that has an impact on the city”.

BIOLAB LISBOA

Rua Maria da Fonte, 4 – Mercado do Forno do Tijolo

biolablisboa.pt

It was born in 2022 as a spin-off of FabLab and with sustainability in its DNA. It is a research, experimentation and prototyping laboratory, whose operation is ensured, in partnership, by the Lisbon City Council and the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Lisbon. Open to all citizens, it prioritizes ideas and projects that bring added value to the city, as Rafael Calado, the coordinator of the space, tells us.

Access to the laboratory is by invitation, spontaneous application or during open days that take place every Thursday. You don’t need to be a scientist or have knowledge of science, as Calado says, recalling the case of a Repair Café regular who asked for help to create soap packaging from almond shells. However, many researchers from various areas of knowledge seek out BioLab to develop their projects.

Currently, and at the proposal of the team that runs this space, a group of designers is experimenting with algae in prototypes of utilitarian objects. The laboratory has 3 levels of biological safety and an ethics charter that defines the limits of what can and cannot be done here.

Maria Lamas (1893–1983) was perhaps one of the most notable Portuguese women of the 20th century. Although a certain memory persists of her political affirmation and action as a communist militant during the Estado Novo and her “self-exile” in Paris, the truth is that her literary and journalistic work is practically forgotten, with very few of her books available in the market. Even less remembered is her side as a photographer, impressive indeed, as Jorge Calado says, “due to such a large number of masterpieces” in such a short collection.

“Extraordinarily modern”, Maria Lamas’ photographs had never been exhibited in Portugal, and are now the focus of this exhibition. As Mulheres de Maria Lamas brings together a selection of 65 of the photographs that she captured, essentially, in rural areas in the center of the country.

Exemplary testimonies of the condition of Portuguese women during the Salazar dictatorship, mostly vintage samples (of the time), small in size, but also some enlargements, the exhibition also displays evidence from the time of other photographers, such as Adelino Lyon de Castro, Artur Pastor or Maria T. Mendonça, included, alongside those by Lamas, in As Mulheres do Meu País, a work published for the first time in installments between 1948 and 1950.

Despite the list of illustrious photographers featured in the book, Lamas’ photographs stand out for their truth and vivacity, constituting in themselves an absolutely unique work in the history of Portuguese photography. Surprisingly, she became a photographer almost accidentally, imbued with her spirit as a militant fighter and opponent of the regime. “She had never taken photographs and used the most basic camera available, the Kodak box model, which did not allow for the possibility of focusing”, recalls Calado.

In addition to the images, personal objects of Maria Lamas are also on display, as well as her portrait painted by Júlio Pomar, in 1954, and the plaster bust sculpted, in 1929, by Júlio de Sousa. The section dedicated to literary and journalistic works includes copies of first editions of the author’s fundamental works, namely in the field of children’s literature, poetry and fiction, translations of classics of youth literature and some journalism.

Although he is here in the role of the curator, professor Jorge Calado does not hide the emotional side with which he designed this exhibition. For him, Maria Lamas is a “heroine”, “the most notable Portuguese woman of the 20th century”, never failing to highlight “her genius” in her work and life. “I have admired her since I was a boy. And, as I grew up, she became an even greater hero, largely due to her opposition to the dictatorship”, he says, adding that, “on the other hand, I also admire her a lot for having been a generous and loving woman in her relationships, not only with family but also with friends. She was an admirable person, always ready to help others.”

Therefore, the exhibition seeks to “reveal a relatively unknown side of Lamas, as well as honor the woman she was”. “Maria Lamas fought to liberate women, not as women, but as citizens and as human beings. It wasn’t about women’s rights, it was about human rights,” he adds. The Women of Maria Lamas is open to the public until May 28.

When São Luiz reopens in September, after the summer holidays, attention will focus on the return to the municipal theater of Brazilian playwright, director and director Christiane Jatahy.

Revealed in Portugal at the beginning of the century, Jatahy has been a constant presence in the European theatrical circuit, highlighting the status that Lisbon attributed to him, in 2018, as Artist in the City. Noted for his versions of the classics of Strindberg and Chekhov, Jatahy stands out in the particularly inventive, and even radical and subversive way, as it combines the languages of theater and cinema.

Recently distinguished in Venice with the Golden Lion, Jatahy presents The Now That Takes Time: Our Odyssey II, successor of Itaca (2018), a show premiered precisely in Teatro São Luiz, and which follows the very particular look of the creator on The Odyssey of Homer.

Regarding disturbing and creative forms of dialogue between theater and cinema, on April 6 and 7 next year, São Luiz presents, for the first time, a creation of the most noteable Katie Mitchell. In a co-production with the Berlin Schaubühne, Virginia Woolf’s chilling classic Orlando is translated into a “live cinema” version where all of Mitchell’s virtuosity is shaped in the technical domain and in the scene, in what will most likely be one of the most anticipated moments of the theatrical season in Lisbon.

Still on the international level, another return to Lisbon: Pippo Delbonno. The Italian director was challenged by Teatro São Luiz to create a show about the city of Tagus, while exploring its connection with Africa, especially Cape Verde and Angola.

It was one of the priorities of the current artistic direction of São Luiz to seek to give, over the years, a growing role to female creators. This season, Beatriz Batarda revisits a musical comedy she directed in the main theater room in 2011, with texts by Karl Valentin. More than a decade later, the director presents, with the same cast (Bruno Nogueira and Luísa Cruz, who now joins Rita Cabaço), Another Bizarre Salad (February 2023).

Other featured creators are Cucha Carvalheiro, with the premiere of the original of his own Fonte da Raiva, which she owns alongside a luxury cast, where they score Filomena Cautela, Manuela Couto or Sandra Faleiro; Olga Roriz, who choreographs an emblematic play by the German playwright Peter Handke, The time when we knew nothing of each other; and Rita Lello in Isadora, Fala!, a solo dedicated to the American dancer, forerunner of modern ballet, Isadora Duncan.

The full program can be found on the São Luiz Teatro Municipal website.

It was the roaring ’20s. Europe was leaving behind the war and the Spanish flu pandemic, incoming a period of euphoria. In The Lisbon of the First Republic, and although it was a peripheral capital, artistic and cultural life began to swarm with the fashions arrived from major cities such as Paris, London and New York.

But if Lisbon also longed to dance the charleston and the foxtrot, the popular taste continued seduced by carousels and wax figures, pim pam pum stalls and target shooting, tascas, displays of master animals and “freaks” of fair, animators and saltimbancos.

It was to seek to recreate the atmosphere of the traditional popular fairs that have been swarming the city since the 19th century, adding it to the breath of sophistication of the times, which, at the back of the Lima Mayer Palace (now the Consulate of Spain in Lisbon), more specifically in its garden, the so-called Sociedade Avenida Parque, led by theatrical entrepreneur Luís Galhardo, inaugurated, on June 15, 1922, the Parque Avenue, or Parque Mayer fair.

The triumph of Revista à portuguesa

Those days, teatro de Revista, or Revista à portuguesa, was a theatrical genre of markedly popular taste, with lots of music and several comic scenes, and everybody loves it. On July 1st, 100 years ago, Parque Mayer saw the first of its theaters, the Maria Vitória Theater, open its doors, with Lua Nova [New Moon].

Interestingly, the first of the theaters to open was the one that, in Parque Mayer, almost uninterruptedly remained in operation over these 100 years, even though it was beset in 1986 by a violent fire. Currently, and at the initiative of Hélder Freire Costa, Teatro Maria Vitória remains the last bulwark of the magazine theater in Lisbon, debuting, year after year, a new show of Revista à portuguesa.

On July 8, 1926, in Parque Mayer opened a new theater, the Teatro Variedades [Varieties], with the premiere of the show of Revista Pó de Arroz. Alongside the stalls of food and drinks, fado and fashion dances, Parque Mayer was increasingly the place of excellence of fun and bohemia in the city of Lisbon.

Then, and always under the aegis of Revista à portuguesa, a genre that so caryby by Estado Novo became a school of opposition and resistance to political censorship and customs, opened the Teatro Capitólio (built in 1931 and rehabilitated and reopened in 2016) and the Teatro ABC Theater (founded in 1956, demolished in the 1990s and transformed into a car park).

The desire for experimentation, taking risk and “not even being afraid to fail” is felt at every moment of Arena, secondcreation of the collective Outro, directed by João Leão and Sílvio Vieira, the latter author of the show. Explain what is going on there, especially when said arena is in an old car workshop located in the heart of one of the residential neighborhoods of the parish of Arroios, it would be like unraveling part of the mystery that surrounds this scenic adventure, where nothing is predictable or neglects the effect of surprise.

However, without pointing out a path, we can reveal the existence of six creatures that move as an organic unit (which the author called Jan), although each plays a role in the collective. Routinely, they undertake a ritual movement, until one day, it will be shaken when, from inside water (literally), an alien character emerges in an astronaut suit.

In arena’s genesis was the premise that it would be a theatre show without a word. “When two years ago, even before the pandemic, we started working on the project it was thought that the pillar would be the translation of music into the theatrical scene. As the choreographer who translates music into gestures, here, the goal was to translate it into theatricality, that is, in images, situations, characters”, explains Sílvio Vieira.

Throughout the creative process, it was precisely from the music that the actors improvised, birthing the essentials of Arena’s situations. But, contrary to the scheduled, something essential happened: the show would not happen in the black box of a conventional stage, but in a garage. “When we got here, I asked the actors to look at the space, choose a corner and try to explore it,” recalls the author, stressing how the architecture of this old abandoned workshop, at 21A Rua Carlos José Barreiros, “entered the dramaturgy of the show itself, being impossible to transport what happens here to another place.”

Without imposing a narrative line or, as the author points out, “any political and ideological concept”, Arena is revealed as an artistic object of full freedom, “where what has been valued is experimentation and the search for beauty, or a certain poetry. As the dipositive is opened, any viewer can read as they see fit. And that’s something I like about a show,” Vieira recalls.

This scenic adventure that combines with great ingenuity and irreverence movement, sound, light and an imaginary whole claimed of silent cinema and the great names of comedy, such as Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton or Harold Lloyd, is starring young actors Anabela Ribeiro, André Cabral, Catarina Rabaça, Inês Realista, Miguel Galamba, Miguel Ponte and Pedro Peças. In the course of the cultural association Outro, born in 2018, Arena is the successor of As trees let die the mostbeautiful branches, a show also written by Sílvio Vieira, premiered in 2020 at the Temps d’Images Festival.

1 – Monteiro-Mor Botanical Park

The park has a vast collection of botanical species. Here is the first araucaria heterophylla known in mainland Portugal. Among the existing fauna, birds and a colony of bats are worth noting.

http://www.museudotraje.gov.pt

Largo Júlio de Castilho – Lumiar, 1600-483 Lisbon

Tel. +351 217 543 920 (box office)

Museum and Botanical Park Hours: Tuesday to Sunday, 10 am to 1 pm and from 2 pm to 6 pm

Closed to the public: Monday, January 1, Easter Sunday, May 1, municipal holiday (June 13), 24 and 25 December.

2 – Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Garden

Built in the 60s of the twentieth century, it is one of the most representative gardens of modernism in Portugal. Inspired by the Portuguese landscape, its ecological and cultural dimension, it has undergone transformations over time. It developed into a dense and varied forest, including a lake and reflecting, as a whole, an idea of paradise. Several trails are proposed: from light and shade, from the lake, from the waterfront, from scents and views.

https://gulbenkian.pt/jardim/

Av. de Berna 45A, 1067-001 Lisbon

Phone: +351 217 823 000

Opening hours: Open every day from sunrise to sunset.

3 – Eduardo VII Park/Cold Greenhouse

Built in the 1st half of the XX century, is the largest park in the center of Lisbon. It has a central strip, covered with grass and Buxus, bordered by walks and green areas. To the northwest of the park is the Cold Greenhouse and, to the east, the Carlos Lopes Pavilion. To the north is a viewpoint with a wide view over Lisbon, the Tagus River, and the other bank.

https://informacoeseservicos.lisboa.pt/contactos/diretorio-da-cidade/parque-eduardo-vii

Eduardo VII Park. 1070-051 Lisbon

Park hours: 24 hours

Cold Greenhouse: Summer, from 10 am to 7 pm.

Closes on January 1, May 1 and December 25

http://estufafria.cm-lisboa.pt/

Tel. +351 218 170 996

4 – Lisbon Botanical Garden

Scientific garden, opened in 1878, is part of the National Museum of Natural History and Science. Among others, it has several tropical species natural from New Zealand, Australia, China, Japan and South America, a wide variety of palm trees originating from all continents, and cycads, currently rare and one of the ex-libris of the Garden.

http://www.museus.ulisboa.pt/jardim-botanico

Rua da Escola Politécnica, 58, 1250-102 Lisbon

Tel. +351 213 921 800

Schedule: Every day except January 1 and December 25.

Winter: 10 a.m. to 5 pm | Summer: 10 am to 8 pm

5 – Jardim do Príncipe Real

A romantic and English-inspired garden, it was built in the mid-19th century, around an ectogonal lake. It has several elements of stactand of the various tree species existing in the garden, stands out the large and secular cedar-of-Buçaco with more than 20 meters. The space has several equipment, including kiosks, terrace and playground. Underground is the Patriarchal Reservoir, belonging to the Water Museum.

https://informacoeseservicos.lisboa.pt/contactos/diretorio-da-cidade/jardim-franca-borges

Praça do Príncipe Real, 1250-096 Lisbon

Time: 24 hours

6 – Jardim da Estrela

The Guerra Junqueiro Garden, known as Jardim da Estrela, was inaugurated in 1852. Public garden, delimited by railing, was built in the style of English gardens, of romantic inspiration. Inhabited by diverse fauna, the garden has several exotic plants among its diverse vegetation, lakes, waterfalls, statuary, a viewpoint, and a bandstand among other buildings.

https://informacoeseservicos.lisboa.pt/contactos/diretorio-da-cidade/jardim-guerra-junqueiro

Praça da Estrela, 1200-667 Lisbon

Time: Every day, from 7 am to 12 pm

7 – Tropical Botanical Garden

This scientific garden was created in 1906 to support the teaching of tropical agronomy. It has relevant botanical collections with about 600 species, mainly of tropical and subtropical origin, especially rare species such as cycas and encephalartos. From the built heritage dating from the 17th century to the 20th century, the Casa do Fresco, the Calheta Palace and the Main Greenhouse are worth highlighting.

https://museus.ulisboa.pt/jardim-botanico-tropical

Largo dos Jerónimos, 1400-209 Lisbon

Tel. +351 213 921 808

Schedule: Every day except January 1 and December 25.

Winter: 10 a.m. to 5 pm | Summer: 10 am to 8 pm

8 – Ajuda Botanical Garden

Founded in 1768, it is the first Botanical Garden in Portugal. The architecture of the garden is of Renaissance model and the ornaments are of baroque influence. Organized on two terraces, it overlooks the Tagus River and is inhabited by peacocks and other birds. It has more than 1600 plants, including a dragon tree with more than 400 years.

http://www.isa.ulisboa.pt/jba

Calçada da Ajuda s/n, 1300-011 Lisbon

Tel. +351 213 653 157

Schedule: Weekdays, from 10 am to 5 pm. Weekends and public holidays from 10 am to 6 pm

Daylight saving time: Weekdays from 10 am to 6 pm. Weekends and holidays from 10 am to 8 pm

Closes on January 1 and December 25

Create “a place of love” to claim what is human, in a time of dehumanization, even more accelerated by a pandemic. This is the purpose of the third edition of BoCA,which begins in Lisbon, Almada and Faro in early September, extending until October 17.

More than a festival, this year 2021, BoCA seeks, in the words of artistic director John Romão, to keep “alive its mission in support of new languages, privilegiem the spaces ‘between’ – for example, between the performative and the visual – new commissions to Portuguese and foreign artists, in trans dialogue (therefore, transgender in all its meanings) implementing projects that propose a new awareness and models between artistic practices and sustainability.”

Goal to be realized through artistic projects signed by dozens of notable creators who seek to look at the world and question established narratives. And, taking into account “a program that combines different rhythms of projects and relationships with artists and institutions, relying on a transition of production and creation processes, integrated, plural and sustainable”, the biennial reinforces the presence of “short-term projects that reinforce the artistic and ethical commitment to artists and production structures , creations that extend in time and space through greater commitment to the short ephemerality of theater and performative, sustainable and long-term relationships with artists and projects, deepening of reflections and long-term processes that combine performivity, visuality, activism and neuroscience, a focus on the direct relationship and representativeness of local communities , artistic, associative and diverse sectors, whose active participation is involved in the creative development of projects to also start an interrelational ecosystem between art, sustainability and science through the project The Defense of Nature.”

This last purpose will be developed in what is a ten-year project, which, in a first stage, proposes, by December this year, to sponsor the planting of 7,000 trees of indigenous species, through the will of 7,000 artists/citizens. From an artistic point of view, this project already includes in this edition a series of performative actions in natural spaces of the three host cities entitled Quero Ver das Montanhas. Curated by Delfim Sardo and Sílvia Gomes, the various performances are starring artists such as Sara Bichão, Diana Policarpo, Dayana Lucas, Gustavo Sumpta, Gustavo Ciríaco, Musa Paradisiaca and the collective Berru.

Lisbon programming

As usual, boca does not settle in Lisbon, and if in previous editions it has “decentralized” the cities of the north of the country, this year crosses the Tagus, settles in Almada, and goes south, to the Algarve, to the city of Faro.

Throughout the capital, the start of the biennial begins with the first large-scale installation of Grada Kilomba, which extends along the river for 32 meters long, in the Coal Square of MAAT. Barco/The Boat proposes to launch “a new collective narrative in this same public space, built from the history of dehumanization, violence and genocide of African and indigenous peoples.”

Meanwhile, at the National Museum of Ancient Art, German artist Anne Imhof presents the video installation Untitled (Wave) in the Alberta Chapel, a place previously inhabited only by women in seclusion; and at Palácio Pimenta, rapper Capicua debuts as a theater author and directs actor Tiago Barbosa in The Junk,“an emotional dissertation that departs from the story of a man who stands alone, in the long months of confinement, surrounded by inert matter, rubble and memories.”

Regarding theater premieres, the BoCA brought to Lisbon the renowned American filmmaker Gus Van Sant, who presents, from September 23, in the Garrett Room of the Teatro Nacional D. Maria II, his first stage creation with a fully Portuguese artistic team. Andy is a musical that “reconstructs the past of an Andy Warhol in early career, through a fictional narrative constructed from real facts and memories, but also from imagination.”

Lisbon will also be the “stage” of The Third Reich, a performative video installation of what is one of the biggest names in European theater, the Italian Romeo Castellucci (National Coach Museum, 9 and 10 September); performance/installation Overlapses, Riddles & Spells, by Andreia Santana (CCB, September 9-12); of the dream videos of Polish Agnieszka Polska present in The New Sun (Patriarchal Reserve, September 13 to October 17) – she will also be at Casa da Cerca in Almada with another video installation, I Am the Mouth; or Passages, nomadic project of the choreographer Noé Soulier, which explores the relationship between the movement of bodies and the places where they inscribe their actions, and in Lisbon, takes place in the rooms of the National Museum of Ancient Art (September 17 and 18), establishing a dialogue between dancers and sculptural objects.

Another of the highlights of this BoCA is the project signed by filmmaker Pedro Costa with the Tagus Musicians. The Daughters of Fire joins cinema, music and theater to tell the saga of three young Cape Verdean sisters who, arriving at a European port, after another devastating eruption of the Volcano of Fire, go wandering, hand in hand, evoking their secret fears through music and singing. This long-adod show is presented on Capitol Hill on September 17 and 18.

In the Lisbon programming, projects of pairs such as António Poppe and La Familia Gitana, Tânia Carvalho and Matthieu Ehrlacher, Gabriel Ferrandini and Hugo Canoilas, Joana Castro and Mauritius Neves are also included; the lasting performances of Miles Greenberg or Carlos Azeredo Mesquita; and two unreleased films by New Yorker Khalik Allah. The full schedule for the three BoCA cities can be found here.

Valério Romão

Valério Romão spent a large part of his professional life working on computer science. The writer, who graduated in philosophy, became a translator thanks to his passion for reading and writing and “the desire to see in Portuguese a certain text that has not yet been translated. Trying to do what other translators did before me, to incorporate the voice of a certain author in Portuguese culture, making him or her known.” Born in France, where he lived until he was 10, he has a natural ability to translate from French, but he also translates from English – “with the help of a dictionary.” He translates a lot of unpublished poetry. “These are translations that I keep in my drawer and that I do for pleasure, and which I eventually show to a publisher. I am translating the book La main hantée, by the Canadian poet Louise Dupré, who writes in French. I admire her poetry, which I discovered in a French bookstore. I sent her a message saying that I would love to translate the book, adding that I couldn’t pay for the copyright because no publisher would bear the cost. Publishing poetry in Portugal is something you do with print runs of 100 copies and without money. She was very pleased. She said she wasn’t in poetry for the money and was delighted with the idea of an author entering a bookstore, reading her book, and then wanting to translate it and making it known.” Valério Romão’s most recent translation, James Baldwin’s O Quarto de Giovanni (Giovanni’s Room), “was a serendipitous opportunity offered by the publisher for which I had already translated Houellebecq. It was an honor because he is a tremendous author, not only for his literary value, but for all his contributions to the fight for human rights, especially of blacks and homosexuals. It is a very risky book from the 50s, beautifully written by a black homosexual man, with no speech ambiguity at all. Baldwin is one of those authors that make you think, ‘I wish I had met this guy!’ He has amazing courage and clear-sightedness.” As for the work, Romão states that the language in the book is not particularly complex: “A bit in the vein of Hemingway, an expatriate, short sentences, but with a different topic and a different emotional density.” Asked if it is difficult to transpose this simplicity of style into a translation, he says: “It depends on whether the apparent simplicity of the author is just another effect or not. In Baldwin’s case, there is great honesty in the way he writes.” And he concludes with a grievance: “Translators are very poorly paid in Portugal. If you consider the time it requires, the quality you demand from yourself, what you actually get after paying you taxes – this is something you do only for the love of it, or because you don’t know how to do anything else.”

Margarida Vale do Gato

Margarida has a degree in Modern Languages and Cultures, but her encounter with translation began before she went to college. At the age of thirteen she moved with her family to California, where she stayed while her father was doing his master’s degree. “I already loved languages back then. I used to wonder how people thought in different languages. I enrolled in a local school, and after a few months I started dreaming in English. This brightened up my days, which were a bit lonely because it’s not easy to move to another country at that age. I knew I would be coming back to Portugal soon, so I also started learning French. But it was very rudimentary, so I invested in self-learning by listening to Jacques Brel. My very first translations were of Brel’s lyrics. I soon realized that this was an activity in which I felt really comfortable.” She does not translate from French at this point, unless it is a poem – “not because it’s easier, but because there’s a concentration in words that requires a different kind of attention, one that does not involve the language’s everyday use. To translate novels you constantly have to watch TV shows, which I don’t particularly like, or movies, which I watch more often. Or you have to constantly go to countries where the language is spoken, in the variant you translate from, otherwise things will sort of freeze. Literature is a mechanism of language innovation where you can follow the latest rumors.” Margarida is preparing an anthology of Beat poetry with Nuno Marques and will now bring us a book by Marianne Moore, O Pangolim e Outros Poemas (The Pangolin and Other Poems), which is “the only proposal I ever made to the publisher. I really wanted to translate this book. I am a professor of American Literature and what I like about modernism is authors who experiment. In terms of poetry, I really like to risk understanding the experience through translation. Marianne Moore is a poet who combines curiosity for small lives (the pangolin, a creature that has been greatly abused by our pandemic, or a nectarine and a strawberry, for instance) with the awareness that the act of knowing depends upon previous representations – but of which she seeks to present a different angle through the cadence of language. As an author, she offers a degree of attention to the represented object that goes beyond the realm of the self. My poetry tends to be personal and to play with autobiography in a way that I continue to pursue because I find it interesting, but which she rejects.” With regards to translation, she believes that “it’s very difficult to work with certain kinds of systematization because some texts afford greater literality, which is important to retain their style and strangeness. On other occasions, you have to adapt them. So when it comes to consistency in translation, we should be suspicious of it. We must risk contradicting ourselves, because the unity of the text is something that translation inherently denies.”

Miguel Martins

A non-practicing archaeologist, Miguel Martins started being invited by publishers to work as a translator by virtue of being a poet. Although he also works as a critic for Gulbenkian’s Colóquio/Letras magazine, translation pays most of his bills. He translates from French, English and Spanish and has translated a booklet from Italian – Luigi Russolo’s Manifesto da Música Futurista (better known in English as The Art of Noises), which “was something I did out of love, and it was slower than it would be if I had a real command of the language. I translate all kinds of stuff to make a living, horrible books, self-help books, and so on. Every now and then I get to translate really good things, like Forster or Lorca’s Mariana Pineda, as well as a lot of poetry for literary magazines. Regarding his latest translation – E. M. Forster’s A Máquina Pára e Outros Contos (The Machine Stops and Other Stories), a collection of texts written over a period of 20 years – Miguel Martins says: “To motivate readers I would basically talk about the short story mentioned in the title, a truly fantastic text, written a hundred years ago, which predicts with surprising accuracy many aspects of the current world and its dystopian traits – communication through machines only, people feeling distant from one another, an internet of sorts, and things such as likes on Facebook.” Regarding the job of a translator, he states that “Command of the source language is much less important for a good translation (with more or less work you get there) than command of the target language. At the end of the day, what people read must be written in good Portuguese. That’s why I think that, whenever possible, literary translations should be done by authors. But besides that, translation also implies culture and all sorts of references – historical, scientific, artistic, political. This is where many translations fail. And it is for this reason – although there are some exceptions – that I have serious doubts about the possibility of being a great translator at a young age. Professional translators never know what kind of work they will get next, so this culture should be as comprehensive as possible, notwithstanding the research required in each case. You can’t make a living solely by translating good things. The rates in Portugal are the same whether you’re translating Shakespeare or a Spice Girls biography. But while I can translate 15 pages a day from a crappy book, with a Shakespeare work I will probably not be able to do more than seven lines. Translators who only translate really interesting things either have other sources of income or can’t make ends meet. For me, the problem with this work are the interruptions, the gaps between this translation and the next. If I were working all the time – which is not desirable, as it is very exhausting from a mental point of view, and also because sometimes I need to break free from the style and language of an author before moving on to the next one – it would be a relatively well paid job.”

Hugo Maia

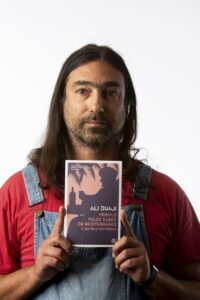

“I started learning Arabic very casually. I had spent holidays in Morocco and I was curious about the language. We understand Spanish, we speak English, but we do not understand the language of a neighboring country which we perceive as being totally different.” Hugo Maia then enrolled in a free Arabic course at Faculdade de Letras and read a lot about the history of the Arab world and the Islamic presence in Portugal. As he was the best student in class, he got a scholarship for a summer crash course in Tunisia. “I realized that in order to learn Arabic, I would have to do it in an Arab country. It was the best way to learn both standard Arabic and colloquial Arabic, so I decided to enroll in the annual crash course in Tunis. In fact, I’m a graduate in anthropology, and I interrupted my degree in 2001/02 to take this course. I’m not an expert in literature. First and foremost, I consider myself a reader. Sometimes I would compare translations from Arabic to French, so I took an interest in translation theory. I realized that there were practically no direct translations from Arabic in Portugal. In 2006 I submitted some translation projects to several publishers, which were refused. Which was fortunate, as my knowledge was not that great. Arabic is not a particularly difficult language, but it is very complex from a sociolinguistic point of view – it has what we call a very pronounced diglossia. There is a standard form of Arabic, which is the same in all Arab countries, and a colloquial form, which is different in every country and even in every region. The differences between the various colloquial Arabic languages are as great as those between Portuguese, Italian, and Romanian. I usually say that in order to learn Arabic well you have to know two languages – standard Arabic and at least one colloquial Arabic language. In the meantime, I lived in Morocco for five years, where I learned colloquial Moroccan Arabic, which helped me translate One Thousand and One Nights, a work that includes many colloquial Arab idioms from the Levant, Syria and Egypt, although these are very different.” When Hugo entered a bookshop in Tunis and discovered Jaoulet Baina Hanet Al Bahr Al Abyadh Al Motawasset (translated in Portuguese as Périplo pelos Bares do Mediterrâneo, which could be translated as A Tour of Mediterranean Bars), he did not know that Ali Duaji was regarded as the founding father of the Tunisian short story. He was fascinated by the author’s irony and sarcasm, which in the 1930s “satirized the new bourgeois classes that were working hand in glove with the political power of the French protectorate, resulting in that very confusing mixture of customs.” But according to him, his latest translation is first and foremost a very peculiar travel account. “A tour of the bars of Europe and Asia that ignores traditional tourist attractions such as museums.” He says he can relate with that and even gives a “shameful” example: he lived for a month right next to the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam and never once visited it. “And I love the painter. I’ve seen his paintings at the Musée d’Orsay!”

Paulo Faria

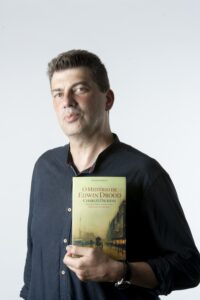

After graduating in Biology, the writer and literary translator Paulo Faria spent some time teaching that subject, but it was “clearly” not what he liked. His grandfather was a language teacher at Colégio Militar and taught him English and French at a very young age. His never lost his passion for literature, which he explored as a self-taught person, and when the opportunity to work on literary translation arose, he did not bail out. He translates from French, but mostly from English. He has translated Emily Brontë, Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, but he points out that when people mention this aspect of his life, they usually refer to him as “the translator of Cormac McCarthy” – an author he particularly admires and from whom he has translated twelve books. “I translated three of them twice from scratch because I found the result of the first translations really annoying when I happened to read them a few years later: Blood Meridian, The Orchard Keeper and Child of God.” The Portuguese Society of Authors presented him with the International Literary Translation Award in 2015 for his translation of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities , and perhaps because of that his name is usually associated with the great classics. His most recent translation is also of a Dickens work – The Mystery of Edwin Drood. This is Dicken’s final novel, and it was left unfinished because the author died while writing it. Because of that, it has “this bizarre thing of being a crime novel in which the mystery remains unsolved. The mystery mentioned in the title thus becomes a double mystery.” Paulo mentions Dire Quasi la Stessa Cosa, a text in which “Umberto Eco argues that a translation can never say the same thing, but if the translator is good it can say almost the same thing. Eco defines translation as an interpretation based on a negotiation. I agree with him. When you are translating an author like Dickens, you must understand what his coevals felt when reading that text – which was natural for them, although not everyone spoke like that – and then try to create a natural artificiality. We cannot replicate the language of that era in Portuguese, nor does a contemporary reader want that. A good translation should reach out to the reader without distorting the original. It’s precisely because of this that translations get old. Every generation translates Dickens or Victor Hugo because our world is no longer their world, but it is not the world of translations from the 1940s either. As an author, when I write a novel, I don’t think about the readers. But as a translator, I always do.

paginations here